BY , RN, MS, CCM

DEFINING THE ISSUE

In addition to the surge of patients diagnosed with acute symptoms of COVID, case managers have been faced with transition or care planning for patients experiencing symptoms post-acutely. Planning is complicated by an environment that is decidedly unstable. The goal of this article is to introduce the reader to post-acute COVID case management.

The terms post-acute COVID, long COVID and long-haul COVID are used to reference patients with persistent and severe symptoms and will be considered interchangeable for the purposes of this article. Currently, no definition of these terms is universally accepted.1,2 The UK COVID Symptom Study definition is “the presence of symptoms extending beyond three weeks from the onset of symptoms.”2 Based on literature review, the initial severity of COVID does not seem to correlate with presentation of long-haul symptoms. Not all patients with extended symptoms were hospitalized at the onset of symptoms, and post-acute symptoms can occur with mild disease. Long COVID has been seen in the elderly, the young, the chronically ill and individuals who are otherwise healthy.

The UK COVID Symptom Study reports 10% of patients are sick longer than three weeks.1 A recent JAMA article noted only 13% of COVID patients discharged from the hospital were symptom-free, while 87% of patients had at least one symptom 60 days after onset of symptoms and 40% reported worsened quality of life.3

As of July 2021, the United States had 34 million reported cases of COVID-19 and more than 600,000 deaths.4 The WHO reported more than 191 million cases worldwide on July 2021 and more than 4 million deaths.5 If the 10% figure is correct, a substantial number of patients are either currently receiving or will be seeking management of post-acute symptoms of COVID. In addition, it is unclear if this is a new chronic condition. No data yet exists to substantiate the number of patients with permanent symptoms. Long-term respiratory, musculoskeletal and neuropsychiatric sequalae have been reported with other coronaviruses. The pharmaceutical industry is preparing for COVID business to be recurring and long-lasting.6

SYMPTOMS

There are multiple theories as to why symptoms are prolonged, including:

- Inflammatory and immune reactions

- Deconditioning

- PTSD and other mental conditions

- Virus remaining in the body in some form

- Relapse/reinfection due to weak or absent immune response

- Microthrombi

- Regulation of ACE 2 receptors

- Hypercoagulable state

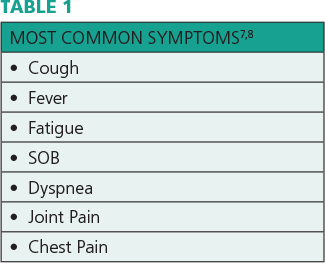

The heart, lungs and brain are most affected, and recovery is gradual and protracted. Highly variable symptoms that wax and wane have been reported. Table 1 lists the most common complaints.

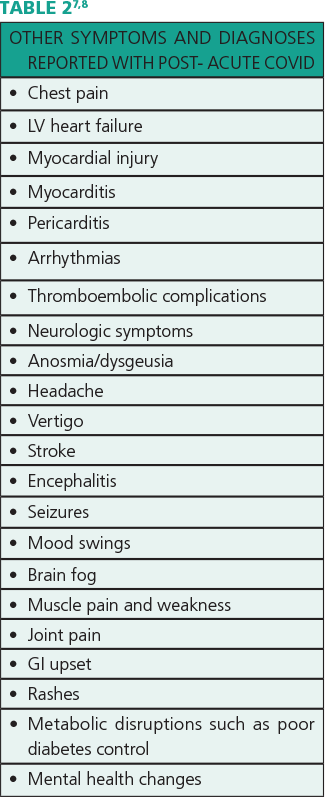

Multiple other symptoms and diagnoses are associated with post-acute COVID, including those listed in Table 2.

This wide range of symptoms can result in significant variation in an individual’s functionality and quality of life. While it would be beneficial for all healthcare sites to use a consistent functional status tool and report to a central database, there is no currently accepted standard. A Post-COVID Functional Status Scale has been proposed that is easy to use but was not validated at the time of this writing.9 A link to the tool is provided for reference:

Early in the pandemic, patients reported their symptoms were not acknowledged by their healthcare providers. Reported symptoms were misunderstood or reduced to anxiety. Patients struggled with credibility. Long haulers found and supported each other on Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms.10,11 By August 2020, long COVID was recognized as a healthcare issue by the healthcare system. This is a compelling reminder of the importance of listening to patients and honoring their story.

BARRIERS TO CARE PLANNING

Transition planning or longitudinal care planning for this group of patients is complicated.12 The trajectory, most appropriate treatment and outcomes are unknown. In addition, the impact the pandemic is having on society is not limited to healthcare concerns. For example, patients may:

- Be grieving the loss of friends or family

- Be experiencing financial stressors due to job loss resulting in housing and food insecurity

- Be undergoing caregiver stress due to isolation and lack of support

- Have deferred healthcare for other conditions resulting in poorly managed chronic or acute conditions.

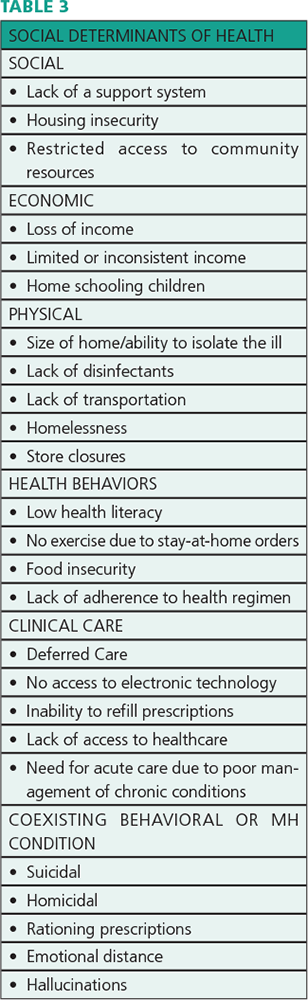

Population vulnerability is a central component of risk exposure and outcomes that is shaped by social, economic and political contexts. Poor, elderly and minority groups have been disproportionately impacted.12 Therefore, it’s important to know the characteristics of the populations you’re serving, as well as fully exploring an individual’s circumstances. Table 3 lists some examples of social determinants of health (SDOH) that can significantly impact the patient’s ability to manage activities of daily living and compliance with a transition or health management plan.

CASE MANAGEMENT

Case management planning is based on the individual’s clinical condition, the availability of needed care, and the patient’s agreement/commitment. A focal goal of case management is to avoid fragmentation of care, and handoffs are especially important for long COVID patients. The CDC issued new interim guidance for healthcare providers in June 2021.13

Due to the nature of long COVID, a multi-disciplinary approach to care planning is necessary. Some medical centers have created outpatient post-COVID clinics, which are often based in pulmonary or family medicine.14,15,16 Rehabilitation is a centerpiece of the care plan, with integrated relationships with neurology, cardiology, dermatology, gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, psychiatry, otolaryngology and sleep medicine, as well as nutrition, nursing, respiratory, pharmacy, financial counseling, social work and case management. These non-traditional programs heavily rely on telehealth, remote monitoring and tele-case management and promote collaboration and partnerships within diverse contexts. Most patients improve in 4-6 weeks, although return to work may need to be phased.

In care planning, patient self-care may include the following elements:

- Pulse oximetry (not cell phone app)

- Diet management

- Rest and sleep management

- Smoking cessation

- Limiting alcohol and caffeine

- Management of comorbid conditions

- Collaboration in setting achievable targets

- Managing oxygen

- Incremental activity increases

- Breathing exercises

- Tele-health appointments

- Tele-case management appointments

- Remote monitoring of pulse oximetry and vital signs

A subset of patients will require longitudinal care planning for chronic disease management, as there is a risk of developing persistent fibrotic lung disease or airway disease. Some patients may be at risk for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. SARS and MERS survivors demonstrated lung changes including change in functional capacity one year after onset of symptoms. Another subset of patients may require care planning for palliative or end of life care.

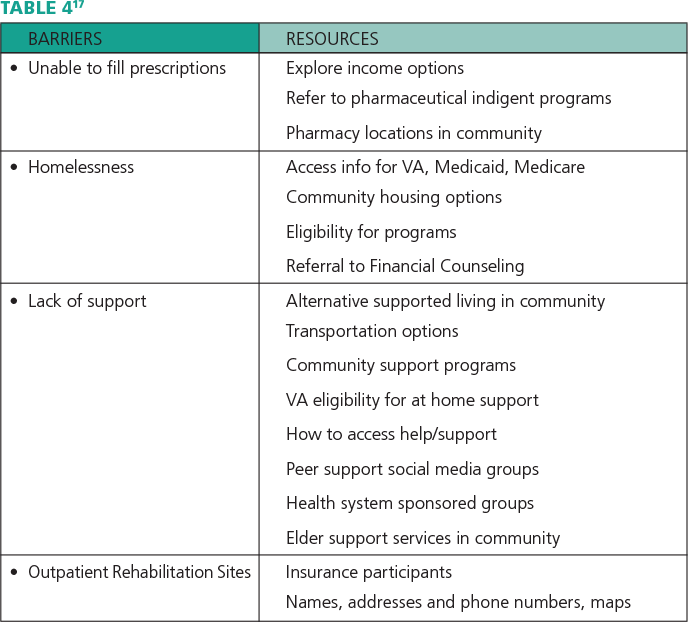

In order for the care plan to be effective, resources should be identified to mitigate barriers to care. Table 4 includes examples of potential barriers and resources for patients.

CONCLUSION

Although there is still much work to be done, it’s encouraging to know effective vaccines exist. When the option is available, prevention is always preferable. To date, over 3.5 billion COVID vaccines have been administered.5

Case managers have a strategic role in the coordination of care for patients and transition planning for patients with long COVID. Whether in an inpatient or outpatient setting, the plan of care for these patients is complex and requires integration of multidisciplinary team planning.18 The societal instability resulting from the pandemic requires multidisciplinary mitigation plans to address barriers to care. The volume of patients and duration of symptoms is uncertain, but the current and anticipated need for care coordination is abundantly clear.