Defining and Describing Palliative Care With a Focus on Case Management

BY , MS, APRN, GNP-BC, ACHPN

Gerald is an 84-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease, a history of CVA, atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation, anemia and is hard of hearing. He has been hospitalized twice in the past 6 months due to severe anemia that is likely due to gastrointestinal bleeding, though a specific source of bleeding has not been identified during his medical workup. He has required blood transfusions during each of these hospitalizations. He is followed by his primary care physician, a cardiologist, a gastroenterologist and a neurologist. He lives in his home in the community with the support of private caregivers and his elderly sister, who is also his healthcare proxy (durable power of attorney). He has expressed that he does not want to return to the hospital. He and his sister both want to know how his anemia can be managed in the outpatient setting. He has not completed an advance directive like a MOLST or POLST order.

Maria is a 48-year-old woman with a history of cervical cancer who was successfully treated with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. There is no evidence of disease, and she is no longer actively followed by her oncology team. Her cancer treatment has left her with disability due to chronic lower extremity lymphedema and severe pelvic pain, for which she requires high-dose opioids for pain management. Maria has bipolar disorder and anxiety. She is now also starting hemodialysis due to the progression of her renal failure. Her primary care physician no longer feels comfortable prescribing her opioids given her increasing medical complexity and need for close monitoring. She lives with her partner in the community who works full-time and otherwise has limited social supports.

As you read these case examples, think about the following:

- What is the role of the case manager in addressing the palliative care needs of this patient and family?

- What is the role of palliative care in addressing the needs of this patient and family?

- In what settings can palliative care be provided?

WHAT IS PALLIATIVE CARE?

Palliative care is a human right. Palliative care is specialized care for patients living with serious illnesses and is focused on providing relief from distressing symptoms and improving the quality of life of patients and families who are facing the stressors and challenges of living with serious illness. Palliative care specialists focus on preventing and relieving suffering through a holistic approach to patient and family care by addressing issues that are physical, psychosocial and spiritual in nature. Palliative care focuses on what is most important to patients and their families—it is whole-person family-centered care (Center to Advance Palliative Care, World Health Organization).

Palliative care is appropriate and should be provided to patients of all ages, at any stage of a serious illness and across care settings. It is available to people in hospitals, clinics, skilled nursing facilities, assisted living communities and in patients’ homes. In the U.S., most specialty-level palliative care services are provided to individuals who are admitted to the hospital, with 94% of hospitals with more than 300 beds and 72% of hospitals with 50 or more beds providing some level of palliative care services (CAPC, 2019). There are geographic variations in the availability and quality of palliative care services. The majority of individuals in the Northeast and Mountain West have almost universal access to palliative care services in hospitals compared to only one-third of hospitals providing this care in the Southcentral U.S. (CAPC, 2019).

Individuals living in rural areas are much less likely to have access to palliative care compared to people living in urban areas. Palliative care services in the outpatient and community setting are becoming more available, and more healthcare organizations are providing community-based palliative care to patients who have serious illness and are not ready or eligible for hospice services. In 2019, CAPC published their report Mapping Community Based Palliative Care, finding that community palliative care programs are operated by a variety of organizations and service providers, with the majority of programs being run by hospitals or hospice organizations. Home health agencies, long-term care facilities and clinics are also providers of community palliative care services. There may be significant variability of palliative care services available in your community. It is important to explore and understand your health system and community’s palliative care resources. One way to explore these resources is to use the palliative care provider registry at https://getpalliativecare.org/howtoget/find-a-palliative-care-team/.

Key Points:

- Palliative care support is appropriate for any patient living with serious illness.

- Palliative care support can be provided at any stage of a serious illness.

- Palliative care support does not limit a patient’s treatment options.

- Palliative care support does not replace their primary medical care.

- Palliative care can and should be provided by any clinician who is involved in the care of a patient with serious illness.

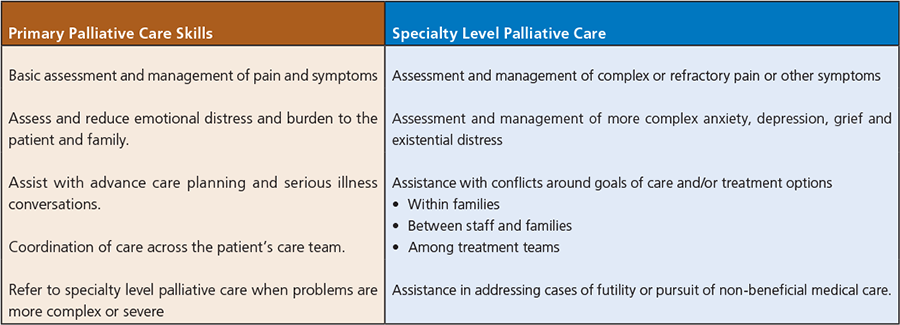

DESCRIBE PRIMARY AND SPECIALTY LEVEL PALLIATIVE CARE

Palliative care is meant to be interdisciplinary and provided by a team of clinicians including physicians, nurses, social workers, spiritual care providers, pharmacists, psychologists and case managers. There is and always will be a need for palliative care specialists to lead, provide specialized care and focus on the most complex needs of patients living with serious illness. We also know that there are not enough palliative care specialists (physicians, nurses, social workers, spiritual care providers) to provide for all of the palliative care needs of all patients living with serious illness. All clinicians need to be able to assess and manage the primary palliative care needs of patients living with serious illness and to recognize when it is time to refer to specialty-level palliative care providers and teams. The effects of COVID-19 have highlighted how crucial it is for every clinician to gain the fundamental knowledge of palliative care and primary palliative care skills.

Primary (or generalist level) palliative care skills are the skills that all clinicians, regardless of specialization or role, should understand and have competence in order to address the complex and long-term needs of patients who are living with serious illness.

Adapted from Kavalieratos et al., (2017) and Quill, T. & Abernathy, A. (2013).

WHAT IS SERIOUS ILLNESS?

There is no one agreed-upon definition of serious illness, but we do know that serious illness carries a high risk of mortality and negatively impacts a person’s daily functioning and/or quality of life and/or excessively strains the caregivers. The Institute of Medicine’s report, Dying in America, tells us that there is an increasing number of elderly Americans with some combination of frailty, physical and cognitive disabilities, multiple chronic illnesses and functional limitations. Cultural diversity is increasing in the U.S. population, and organizations and clinicians must be prepared to provide culturally safe care. We must recognize structural barriers that create inequity in access to palliative care for underserved populations and work to connect patients and families with the services they need and can readily connect with. This report also highlights structural issues that create barriers to meeting the needs of patients with serious illness, including waste in the utilization of resources, misaligned financial incentives, a fragmented care delivery system, time pressures that limit communication with patients and families and a lack of service coordination across programs.

WHAT ARE THE NEEDS OF THE SERIOUSLY ILL?

The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (2018) highlight the needs of individuals who are seriously ill. We have numerous opportunities across care settings to address these needs, and case managers are uniquely positioned to influence care delivery.

- Individuals who are seriously ill need care that is seamless across settings, can rapidly respond to needs and changes in health status and is aligned with patient-family preferences and goals.

- Providing “crisis care” to individuals with a serious illness whose ongoing care needs are poorly managed has resulted in increased health care spending that does not necessarily improve QOL.

- Care of individuals with serious illness is often marked by inadequate symptom control and low patient and family perceptions of the quality of care; and potentially discordant with personal goals and preferences.

- Patients with serious illness and their family caregivers are seldom able to have their care needs reliably met, leading to symptom exacerbation crises and emergency department visits and/or repeated hospitalizations.

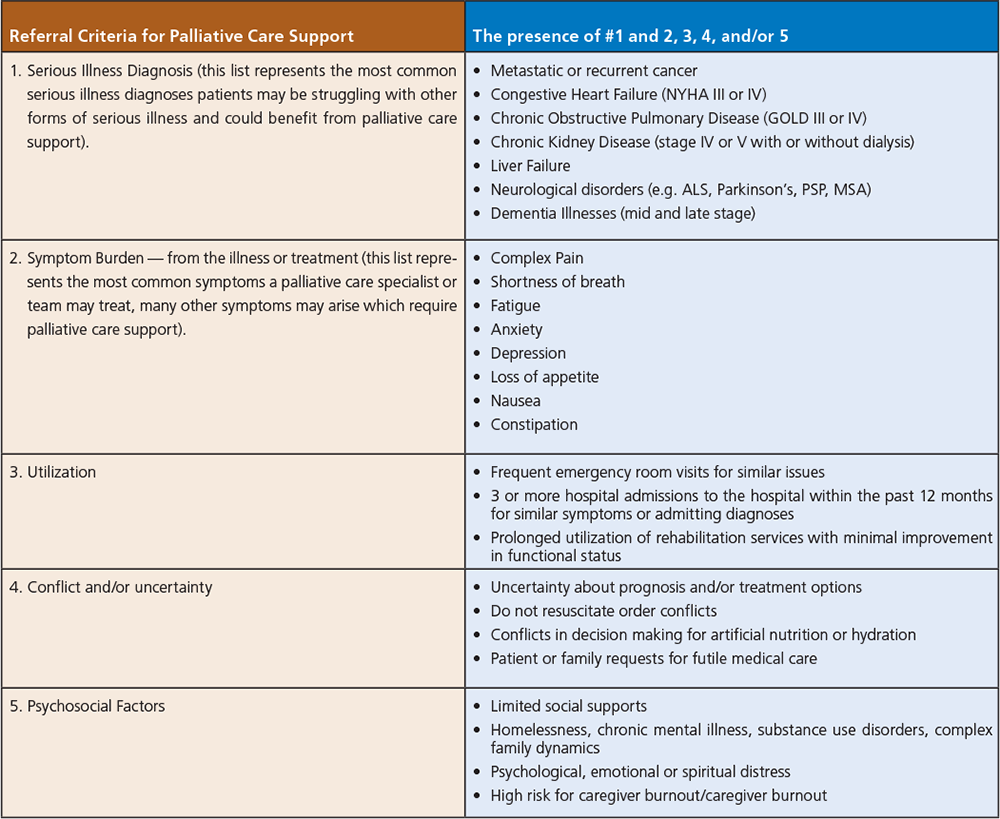

THE ROLE OF THE CASE MANAGER IN PALLIATIVE CARE

Case management consists of assessment, planning, implementing, coordinating, monitoring and evaluating the services and options required to meet a patient’s health and service needs (van der Plas et al, 2012). Case managers have a vital role to play in addressing the palliative care needs of patients living with serious illness. Case managers influence care decisions and can be incredible advocates and change agents. It is important for case managers to acquire primary palliative care knowledge and skills and to be able to effectively assess for physical and psychosocial issues and screen for unmet health needs in patients with serious illness. Case managers do not establish diagnoses or make treatment decisions, but they do advocate for and guide referrals to appropriate specialty-level palliative care resources when needed.

At least half of patients experience one or more transfers in their last month of life (van der Plas et al.), which illustrates the incredible need for effective communication and coordination of care that is required to ensure dignity, comfort and wish-concordant care at the end of life. The completion of advance directives is an important component in ensuring that patients are not burdened with inappropriate transitions in care as they near end of life and that they are not subjected to burdensome medical treatment that is not in line with their values and wishes. Ariadne Labs offers serious illness conversation training and conversation guides that are incredibly rich and practical resources. (https://www.ariadnelabs.org/access-serious-illness-conversation-guide-training/ and https://www.ariadnelabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SI-CG-2017-04-21_FINAL.pdf)

Initiating advance care planning and serious illness conversations is another critical area where case managers can be influential in the care of people living with serious illness.

Case managers can explore patient and family understanding of serious illness and treatment options, identify psychosocial and emotional needs of patients and families as they work through these conversations and decisions and provide an extra layer of support and follow-up for patients and families who may experience a higher level of anxiety during these conversations. Case managers also play a pivotal role in alerting primary care providers when patients and families express readiness to complete advance directives (e.g., MOLST or POLST orders), when a patient and family require follow-up to address prognosis and treatment options, when a family meeting may be necessary to address conflict around medical decision making and when a referral to a specialty-level palliative care provider would be beneficial to provide adequate support to the patient and family.

CONCLUSION

As we return to the cases of Gerald and Maria, think about how you would approach assessing and addressing the palliative care needs of both of these individuals. How would you approach your role as the case manager and apply the principles of primary palliative skills to these cases? What would inform your decisions to guide referrals to specialty-level palliative care clinicians? Where could each of these patients receive palliative care services along their journey, and how would you identify the palliative care resources in your organization and community?

Case management’s role in the care of people with serious illness should be focused on maintaining continuity of care, addressing physical, psychosocial and spiritual needs, understanding patient preferences for treatment and advocating for and guiding referrals to appropriate resources including palliative care specialists. Case managers are also highly influential in coordinating care and ensuring that primary care providers are aware of and informed of their resources to address the primary and specialty level palliative care needs of their patients and families living with serious illness.

Adapted from, Is Palliative Care Right for You, www.getpalliativecare.org and Palliative Care Referral Criteria, CAPC

REFERENCES

Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC). (2019). Mapping community palliative care: a snapshot. Accessed from: https://www.capc.org/documents/700/ on Sept 27, 2021.

CAPC. (2019). America’s Care of Serious Illness: A state-by-state report card on access to palliative care in our nation’s hospitals. Accessed from: https://reportcard.capc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CAPC_State-by-State-Report-Card_051120.pdf on Sept 21, 2021.

CAPC. Palliative Care Referral Criteria. Accessed from: https://www.capc.org/documents/286/ on October 3, 2021.

Get Palliative Care. Is Palliative Care Right for You? Accessed from: https://getpalliativecare.org/rightforyou/ on October 3, 2021.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2015). Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press: https://doi.org/10.17226/18748.

Kavalieratos, D. et al. (2017). Palliative care in heart failure: rationale, evidence, and future priorities. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 70(15), 1919-1930. https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jacc2017.08.036

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th edition. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp

Quill, T. & Abernathy, A. (2013). Generalist plus specialist palliative care – creating a more sustainable model. The New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 1173-1175. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620.

van der Plas, A., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B., van der Watering, M., Jansen, W., Vissers, K., Deliens, L. (2012). What is case management in palliative care? An expert panel study. BMC Health Services Research, 12, 163. https://doi/org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-163

World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Palliative Care. Accessed from: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care on Sept 21, 2021

SUGGESTED RESOURCES

Get Palliative Care Provider Directory: www.getpalliativecare.org/provider-directory/

The Center to Advance Palliative Care: www.capc.org

Ariadne Labs Serious Illness Care: www.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care/

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: www.nhpco.org

The Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association: www.advancingexpertcare.org

Social Work Hospice and Palliative Care Network: www.swhpn.org