Reflecting on COVID Spawned Mental Health Impact on Healthcare Professionals

BY ROGER ORSINI, MD, MBA, FACS, AND DENNIS ROBBINS, PhD, MPH

COVID-19 vaccinations prevented 3.2 million deaths and 18.5 million hospitalizations in the United States from December 2020 through November 2022 (Reference 1). Those averted medical expenses exceed $1.15 trillion. “Without vaccination, there would have been nearly 120 million more COVID-19 infections.” Without vaccination, the modeling indicates, the U.S. would have had 1.5 times more infections, 3.8 times more hospitalizations, and 4.1 times more deaths, (Reference 1).

These stats, while quite impressive, completely ignore the immense mental health debt and impact to our society, especially upon the healthcare workers—nurses and doctors who drive the care and meet the unmet medical and emotional needs of those whom they serve, as well as the support staff that many times suffer the hostility of frustrated patients and their families.

Look at some of the titles of news articles pointing out the difficult times that clinicians have had to cope with daily:

- Analysis of Doctors’ EHR Email Finds Infrequent but Notable Hostility (Reference 2)

- Bullies in white coats? ‘Too many’ health care workers experience toxic workplaces, studies show (References 2 and 3)

- Of those surveyed, 76% of the people said they experience incivility in the workplace at least once a month (Reference 4)

- Health care and social service workers were five times more likely to experience workplace violence than all other workers (Reference 5)

- Confronting the Growing Violence Against Staff in the Emergency Department Problematic (Reference 6)

- Alcohol Use on the Rise Among Physicians? (Reference 7)

Dr. Orsini vividly remembers when a patient who assiduously refused to get vaccinated not only ignored the required vaccination protocol to be seen in his office but also followed him home and, on his evening walk, threatened him at gunpoint!

How many doctors and nurses are walking around with bright smiles on the outside while suffering darkness on the inside? How many of us continue with life without acknowledging the need for or seeking treatment, respite or some other form of help? How many of us are willing to die rather than confront what is overwhelmingly happening inside our heads?

Healthcare professionals profess to serve, and that involves exposing themselves to a great deal of risk. That is part and parcel of their daily routine. We have policies and procedures dealing with protecting ourselves, to avert the risk of getting sick or exposure to things ranging from masking, hand-washing, ventilation, gloving, protective clothing and the like. Early in the COVID era, when people didn’t know what exposure and contraction could mean for them and their families, this created an oppressive and overwhelming degree of uncertainty, fear, ambiguity and discomfort. The mandates for people with young children or those who were immuno-compromised, mysophobic or hyperanxious exacerbated concerns.

Shortages of personnel, equipment, beds and medication all made the experience worse, more uneasy, if not bordering on the impossible. Certainly, navigating the early stages of a pandemic with something that we can understand and can accommodate into our workflow as best we can is not overwhelming. But when we find that people are not doing the things that they can do to avoid getting sick, or avoid putting us and others at risk, exacerbated things beyond more than we would expect of these, way beyond the usual trajectory of an unexpected and unplanned circumstance. None of this was helped by the politicization of COVID, and the unexpected sequalae of these aberrations.

Our history of dealing with pressures upon health caregivers and providing mechanisms or interventions to help them is not a pretty sight. Nurse, physicians and other direct and indirect caregiver burn out, suicide, depression, anxiety and opting out of the profession are not new to us. However, their incidence has become so profound that we need to be cognizant and vigilant of their presence and have mechanisms in place with which to address and ameliorate these risks and events.

Violence against healthcare workers appears to have worsened during the pandemic. During a 3-month stretch in 2022 in the U.S., 57 nurses were attacked each day on average — that’s two nurses every hour — according to a Press Ganey analysis of its National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (Reference 8).

Nurses working in psychiatric units and EDs experienced the highest number of assaults, but nurses in pediatric, burn, rehabilitation and surgery units also were frequently attacked, according to the analysis.

An NNU survey from April 2022 found 48% of nurses polled reported an increase in workplace violence — more than double the percentage over the prior year (Reference 9).

Emergency doctors also experienced increased violence. In 2022, two out of three reported being assaulted in the past year, according to an ACEP survey (Reference 10). At least two-thirds of those surveyed said the COVID-19 pandemic brought increased rates of violence and diminished levels of trust between patients and physicians or other ED staff.

Restrictions on patient visitors or long wait times for care have been cited for triggering violent responses from patients and family members, but there are myriad reasons for the attacks.

It’s also about acceptable comfort zones. As long as things fall within our customary comfort zones, we’re OK. However, when we get to the edges and beyond the edges of those zones and enter unfamiliar terrain, we start getting nervous. When we get outside of the comfort zone, that’s when problems begin to arise. And when we know, as we did early in the game with COVID, that shortages of personnel, equipment, talent and the like put us in precarious situations, then we exceeded what we were comfortable with, and we became anxious and so overwhelmed that many people dropped out of the profession or even became suicidal. Having the emotional and physical resilience to get back in the groove and not be overwhelmed, not become a victim to processes and be able to excel became a critical element. We can’t wait for people, nurses and physicians to raise their hand and say they need help.

Bullying and anger exacerbate this already emotionally fraught area.

Bullying has “been described as the ugly secret in the most caring and compassionate of professions… bullying is pervasive. It’s something we haven’t talked about nearly enough,”. (Reference 11). “More and more, the armor that we put on at the very beginning, and that we’ve aggregated over our time in practice is just not protecting us in the way that it did before,” said Dr. Alika Lafontaine, an anesthesiologist and president of the Canadian Medical Association. AMA member Susannah G. Rowe, MD, MPH, said “it’s far better to prevent or intervene than it is to actually do something about it later. So, the punishment, the reporting systems, the various different systems that we put into place when something has happened are very important, but far less powerful than actually stopping it from starting.” With harassment of doctors on the rise (Reference 12), Drs. Farley, Lafontaine and Rowe shared what actions can be taken to address bullying in medicine.

- Recognize it harms everyone

- Adjust expectations

- Get rid of stupid stuff to reduce administrative burdens by removing low value work through a rapid improvement process.

- Get radical to shore up staffing

- Designate a well-being executive

- EAPs are not enough

An employee-assistance program is not enough to address well-being. Instead, provide quality mental health counseling, establish a peer-support program and offer psychological first aid training for all leaders (Reference 13).

ChristianaCare has offered a unique model to address these concerns. It began a Caring for the Caregiver program, encouraging staff to support each other through difficult times, about 5 years ago. It later established the Center for Worklife Wellbeing (Reference 14) with the aim of fostering work-life meaning, connection and joy. Because ChristianaCare already had these wellness programs in place, the health system was “uniquely positioned” to help clinicians and staff through the COVID-19 pandemic to allow facilities to scale already existing supports. The system provided hotel accommodations, disposable scrubs and scrub changing areas, and offered alternative assignments to pregnant staff and those with underlying health problems. A food bank and a coronavirus testing center exclusively for staff was another part of the mix. ChristianaCare also offered 24/7 mental health resources through its employee assistance program and helped connect staff to peer support (either one-to-one or in a group setting), mindfulness resources, and daily inspirational text messages meant to counter “anxiety-producing stimuli.”

The biggest problems are that most healthcare workers do not acknowledge or appreciate the severity of their mental health problems or are even willing to recognize that they even have a problem.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health and well-being of health care workers (HCWs). “The Health Care Worker Stress Survey” was administered to ambulatory care providers and support staff at three multispecialty care delivery organizations as part of an online, cross-sectional study conducted between June 8, 2020, and July 13, 2020 (Reference 15).

The greatest stress impact reported by HCWs was the uncertainty regarding when the COVID-19 outbreak would be under control, while the least reported concern was about self-dying from COVID-19. Differences in COVID-19 stress impacts were observed by age, gender and occupational risk factors. Approximately 50% of participants reported more than a minimal level of anxiety, including 22.5% who indicated moderate to severe levels of anxiety. Higher levels of anxiety were observed with younger ages and female gender, while occupational roles with increased exposure risk did not report higher levels of anxiety. Roughly two-thirds of the sample reported less than good sleep quality and one-third to one-half of the sample reported other sleep related problems that differed by age and gender. Role limitations due to emotional health correlated with COVID-19 related stress, anxiety and sleep problems.

After weathering the immense difficulties of COVID-19 for the past few years, medical groups and health systems leaders will not receive any respite in 2023. Huge challenges await these leaders in the coming year in many areas — finance, operations, clinical practice, and workforce. Yet, progress is possible as some will leverage the numerous strengths of their organizations to create more adaptable, focused care delivery systems that better meet the needs of their patients, providers, and communities. Here are a few of the critical issues they will be facing.

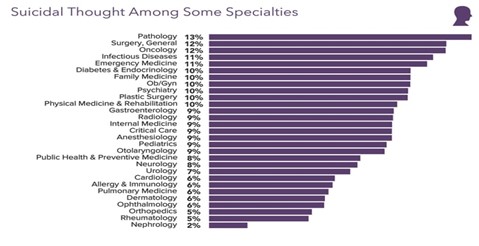

Burnout and depression, stress in and out of the office, and the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic have contributed to many physicians feeling despair and hopelessness, which can contribute to having suicidal thoughts.

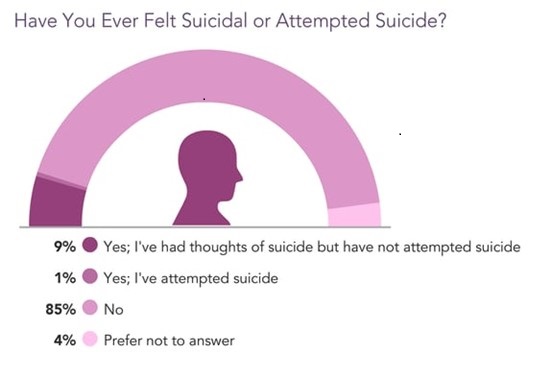

Medscape surveyed more than 13,000 physicians who were frank in sharing their experiences about what led them to consider suicide, how they handled those thoughts, how they try to stay mentally healthy, and how they help colleagues who are going through a dark time. 1 in 10 physicians said they had thought about or attempted suicide. Recent studies (Reference 16) have shown that the rate of suicidal thoughts among physicians is higher than in the general population (7.2% vs 4%).

Slide #2 of 17

Source: Yasgur, Batya Swift. A Tragedy of the Profession: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2022. Medscape. Published March 4, 2022. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-physician-suicide-report-6014970. Copyright Medscape. Used with permission.

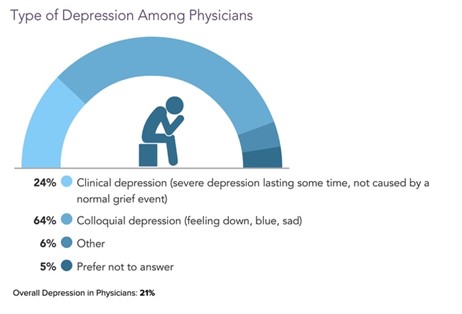

About a fifth (21%) of physicians overall said they were depressed. Of those, 24% noted clinical depression and 64% said they had colloquial depression (Reference 16).

Slide #5 of 17

Source: Yasgur, Batya Swift. A Tragedy of the Profession: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2022. Medscape. Published March 4, 2022. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-physician-suicide-report-6014970. Copyright Medscape. Used with permission.

Slide #3 of 17

Source: Yasgur, Batya Swift. A Tragedy of the Profession: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2022. Medscape. Published March 4, 2022. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-physician-suicide-report-6014970. Copyright Medscape. Use with permission.

Around 1 in 10 physicians said they had thought about or attempted suicide (Reference 16).

Recent studies have shown that the rate of suicidal thoughts among physicians is higher than in the general population (7.2% vs 4%) (Reference 17).

The rate of suicidal thoughts among physicians has declined since Medscape’s 2019 National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report, when 14% of physicians reported having suicidal thoughts; the rate rose to 22% in 2020 but dropped this year. The rate of physicians attempting (but not completing) suicide has remained steady over the years at 1% (Reference 18).

Perhaps COVID has forced, and provided, another opportunity for us to closely examine our routines and habits and take stock of what really matters. Generations expectedly differ in their values and definitions of success. COVID has set prior established rules on fire, by forcing patterns and expectations that were neither expected nor wanted, within the context of a global health crisis. Within this backdrop, should we really believe our worth is determined by our job?

The training of physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners have certain baggage associated with it, one that is the perception or the expectation that we are bulletproof and that we all need to be tough and solve all the problems. An especially difficult expectation during the COVID pandemic where the scenarios were constantly changing-questioning natural immunity versus different vaccines, masks and isolation as more and more patients died or were left on ventilators.

These pressures of the COVID pandemic have made us vulnerable, wounded and fragile. We are left with questions as to how to deal with the uncertainties and how to accommodate uncertainty into our lives.

As physicians, we are thought to be godly, and patients expect us to have the answers, save their lives or the lives of their family members and not let this “virus” win.

The nurses are expected to do everything to make you, the patient or a family member comfortable, to be there at your beck and call and not isolate and contribute to the failure of saving the patient.

As a surgeon both during my training in my practice, I always had at least five options or scenarios in mind when I approached a case. That way I had a game plan with wide range of viable scenarios to allow me to optimize my treatment efforts and ensure safety. That wide range of potentials creates the context for me to perform and get the job done in the right way at the right time and as safely as possible That shapes and falls within my comfort zone. However, when things arise that fall outside your comfort zone, or when the managed care, insurance companies determine your choices or even when you have to submit preauthorizations for treatment delaying treatment you throw your hands up in the air. Said in another way, if you are holding up both hands to prevent the walls from caving in on you, then you can’t let go and do the fine-tuning. This is the reality. This is the frustration that we all, healthcare workers, are dealing with and the pandemic has only made things worse.

All these pressures, the frustration, the bullying, the fear of reprisal, threats and the numbers across the board that there are now shortages of all healthcare workers as they quietly quit (Reference 19) either totally or reduce what they are willing to take on as care givers requires not only reflecting but some concrete actions to make a difference. Things need to change. For me as a caring, experienced and respected surgeon, the pressures and frustration have finally accelerated my decision to quietly retire.

References

- Fitzpatrick,M., Moghadas,S., Pandey, A., Galvani, A.Two Years of U.S. COVID-19 Vaccines Have Prevented Millions of Hospitalizations and Deaths. The Commonwealth Fund. 12/13/2022. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/two-years-covid-vaccines-prevented-millions-deaths-hospitalizations

- Baxter, S., Saseendrakumar, B. R., Cheuug, M.,et. Al. Association of Electronic Health Record Inbasket Message Characteristics with Physician Burnout. JAMA Network Open.2022;5(11). Nov. 30, 2022. http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.44363?utm_source=For_The_Media&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=ftm_links&utm_term=113022

- Sudhakar, Shiv. Bullies in White Coats? Too many health care workers experience toxic workplace, studies show. Fox News. 12/08/2022. Bullies in white coats? ‘Too many’ health care workers experience toxic workplaces, studies show | Fox News

- Porath, Christine.Frontline Work When Everyone is Angry. “76% of people said that they experience incivility in workplace at least once a month.”Harvard Business Review. Nov. 9, 2022. Frontline Work When Everyone Is Angry (hbr.org)

- Sudhakar, Shiv. Health care workers treating each other ‘disrespectively’ on the rise. New York Post. Fox News. Dec. 08, 2022. Health care workers treating each other ‘disrespectfully’ on the rise (nypost.com)

- Skog, Alex. Confronting the Growing Violence Against Staff in the Emergency Department. Reported by Emily Hutte. MedPage Today. 12/30/22. https://www.medpagetoday.com/emergencymedicine/emergencymedicine/101974.

- Wilson, J., Tanuseputro, P., Myran, D., et al. Characterization of Problematic Alcohol Use Among Physicians: A Systemic Review. JAMA New Open.2022; 5(12): e2244679. Doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.44679. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2799353?resultClick=1.

- Patka, Sophie, Violence Against Nurses Worse Than Ever, Analysis Finds. Med Page Today. Sept. 13, 2022. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/features/100679.

- National Nurse United. National nurse survey reveals significant increases in unsafe staffing, workplace violence, and moral distress. April 14, 2022. https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/press/survey-reveals-increases-in-unsafe-staffing-workplace-violence-moral-distress.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Poll: Increasing Violence in Emergency Departments Contributes to Physician Burnout and Impacts Patient Care. Sept.22, 2022. Emergency Physicians.org. https://www.emergencyphysicians.org/press-releases/2022/9-22-22-poll-increasing-violence-in-emergency-departments-contributes-to-physician-burnout-and-impacts-patient-care.

- Farley, Heather. Panel discussion on the issue at the 2022 International Conference on Physician Health. Plenary Session/ Bullying and medicine.

- Lubell, Jennifer. Harassment of doctors is on the rise. Here’s how to stop it.ama.assn.org. July 08, 2022. https://www.ama-assn-org/practice-management/physician-health/harassment-doctors-rise-here-sohow-stop-it

- Shapiro, Jo.; Peer Support Programs for Physicians Mitigate the Effects of Stressors through Peer Support. AMA STEPS Forward. AMA Ed Hub. June 25, 2020. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767766?resultClick=1&bypassSolrId=J_2767766.

- Christiana Care Center for Worklife Meaning Connection and Joy. Post Office Box 1668, Wilmington, DE. 19899. https://christianacare.org/forhealthprofessionals/center-for-worklife-wellbeing/

- Biber, J., Ranes, B., Lawerence, S., Malpani, V., et al. Mental health impact on healthcare workers due to COVID-19 pandemic: a U.S. cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. Springer Open. Published June 13, 2022. https://jpro.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41687-022-00467-6#.~.text=Data%20collection%20for%20an%20onlive%2C%20cross-sectional%20survey%20study%sC.and%20wellmed%20Medical%20Group%20in%20Texas%20and%20Florida.

- Yasgur, Batya Swift, MA. Contributor Information. Medscape Physician Report: The Tragedy of the Profession 2022. Slide #2. March 4, 2022. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-physician-suicide-report-6014970#17.

- Laboe, C., Jain, A., Bodicheric, K.P., Pathak, M.; Physician Suicide in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus Part of Springer Nature. Published Nov. 06,2021. Cureus.202/Nov6;139110:e19313.doi:107759/cureus19313 eCollection. https:www.cureus.com/articles/75951-physician-suicide-in-the-era-of-the-covid-19-pandemic.

- Kane, Leslie,MA.Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report.Jan.16, 2019 Contributor Information. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1.

- Calvery, Margaret, PhD. Commentary-Quiet Quitting: Are Physicians Dying Inside Bit by Biy? Or Setting Healthy Boundaries? Medscape. Sept 16, 2022. Medscape.com. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/980682.

Roger A. Orsin i, MD, MBA, FACS, recently retired as a board-certified plastic surgeon, who practiced reconstructive plastic surgeon for over three decades and spends additional time consulting on practice management, strategic planning and management and lecturing nationally. His abiding interest in the interface between physician, practice management strategies, and optimal patient care outcomes inspired him to pursue graduate business studies at JHU’s Carey Business School, from which he earned his MBA in 2007 and is a former senior adjunct professor at the Carey School of Business in Healthcare Management. He is currently a member of the Legislative Council for the Maryland State Medical Society and the Health Insurance Subcommittee.

i, MD, MBA, FACS, recently retired as a board-certified plastic surgeon, who practiced reconstructive plastic surgeon for over three decades and spends additional time consulting on practice management, strategic planning and management and lecturing nationally. His abiding interest in the interface between physician, practice management strategies, and optimal patient care outcomes inspired him to pursue graduate business studies at JHU’s Carey Business School, from which he earned his MBA in 2007 and is a former senior adjunct professor at the Carey School of Business in Healthcare Management. He is currently a member of the Legislative Council for the Maryland State Medical Society and the Health Insurance Subcommittee.

Dennis Robbins, PhD, MPH, is a catalytic force committed to rejuvenating health/healthcare and committed to creating an actionable platform to shape and engage people to improve their lives, health, and well-being. He wants to help each person become a vanguard rather than victim using AI, innovative technologies, and science. His work on person-centricity™ leverages how we think about the culture of health, wellness, and life, shifting the paradigm from patient to person.

Dr. Robbins has held faculty appointments in medical schools, schools of pharmacy, allied health and dentistry and taught a wide spectrum of courses in medical schools, public policy, and business programs at such institutions as Harvard, Loyola, Singularity, Arizona State, Wayne State, Pepperdine, UNC and NYU. He has been recognized as among the top 100 speakers in the U.S. by the Governance Institute. His legacy of 11 books and more than 400 articles is complemented by a plethora of keynote presentations and panels. His innovations have been recognized in national media such as Forbes, Hospital Ethics and Managed Healthcare, which honored him as among top 10 keenest thinkers in healthcare. To reach Dr. Robbins, email him at [email protected].

IMAGE CREDIT: ISTOCK.COM/PONOMARIOVA_MARIA