Using Research to Advocate for Best Practices

Managing injured or ill working-age people can be complicated when cases have co-occurring conditions or non-diagnostic factors (like the social determinants of health) driving people toward poor recovery outcomes. These complexities consume considerable time for case managers and can lead to longer recoveries, affecting the patient’s mental health and self-identity. Additionally, when managing short-term disability cases, once benefits are exceeded there is a higher risk of transitioning to permanent long-term disability programs or even unemployment, both of which have physical, mental and financial consequences for the patient’s well-being (Wizner et al., 2021).

To identify common barriers faced when managing complex claims and to offer solutions, we conducted a focus group study to identify actionable risk factors. By understanding these influences, we can offer evidence-based, systemic practices that support case managers’ ability to proactively intervene and keep people from going off the rails of recovery.

Our recommendations from this research are that case management organizations should:

- Have leadership designate a point person who will respond when a case manager reaches out.• For example, this can be a human resources person at an employer or a program manager of a clinical staff who can handle requests and understands why quick responses are in the best interest of the patient.

• Offer information important to this point person’s organization, such as job descriptions, benchmark statistics or requests by the patient so that communications are two-way.

- Create workflow maps based on best practices that outline when and how outreach should be done.• This can help staff understand the “big picture,” as well as set benchmarks so that case managers can better see when a patient’s recovery may not be going well.

Training case managers to watch out for red flags, or creating processes to follow best practices, can help keep patients focused on their medical recovery. This study found that experienced case managers already know major reasons why recovery can be delayed by non-diagnostic factors and offered solutions which would be best applied upstream by systemic changes. Currently, case managers are using their own networks to build relationships on an individual basis. But, if organizational leadership made these recommendations a priority, there are many ways to remove these barriers for case managers. This will likely require advocacy on behalf of case managers to see these changes implemented. Hopefully our research helps you build a strong case for changes that will improve patient outcomes as well as job satisfaction and effectiveness for your own work.

RED FLAGS

From focus group discussions with experienced case managers, our analysis found three major themes for determining if a case was likely to go beyond recommended recovery durations because of non-medical factors: multiple information sources, type of condition or workplace culture issues. These “red flags” can help case managers decide early on if a case is likely to become delayed. Umbrellaing these three ideas was the ever-present challenge due to communication barriers, especially between organizations or specialties, which continue to be the bane of workplaces.

The first red flag was if multiple information sources were being consulted, such as the emergency department physician, the family physician, physical therapists and pain management teams. For example, participants said severe car crashes should be handled uniquely because they have so many clinicians providing care that it is difficult to get accurate information to properly manage the case. Participants also stated that if the healthcare systems used a third-party records management system, paperwork was often slowed down.

Furthermore, our case managers said that it is difficult to discuss RTW timelines if the patient’s medical team had not previously discussed it. One participant guessed that it was a “50-50 chance” that a clinician would give a specific recovery timeline based on the condition, and it was even less likely if the care team lacked an occupational health nurse, occupationally trained clinician or vocational specialist. It was especially stressful when the patient didn’t realize that they would lose benefits, and possibly even their job, if they moved from short-term to long-term disability. Often these are emotional conversations that can take several hours. Needless to say, when this task falls to a case manager, it increases their workload.

The second major theme participants cited was that complex cases often followed patterns based on the type of condition. Cases that often become complex are the types of conditions with weak definitions, require conservative care first or have variable care options. Also, if the patient has many comorbid conditions. If these types of cases can automatically go to someone with specific experience or are flagged as a case that will take more time than expected, case managers felt they could be better supported.

The third red flag that participants discussed was if there were workplace culture issues. Case managers may not have access to this information, as neither the clinician nor the patient is required to share work-specific conflicts related to the condition. But a toxic or stressful work environment can be a major barrier to returning someone to work, especially for mental health or behavioral health claims (Hogh & Viitasara, 2005; Shafi et al., 2019). However, when case managers find that the root cause is related to a workplace culture issue, oftentimes the employers have no direct pathway for the case manager to reach out to the patient’s human resource department, which would be better equipped to offer assistance.

This topic was also impacted by the patient’s job type and the employer’s policies, particularly flexible RTW. For example, jobs that require significant physical labor are harder to go back to when recovering from injury or illness, regardless of the type of diagnosis. If employers were more flexible, like offering light duty or alternative job tasks, patients could go back to work in some capacity sooner. This also requires the employers to respond quickly, which is often difficult when working with large organizations. Some patients could go back to work a few days early, but by the time they get approval, and the paperwork is in place, that window of opportunity has passed. Furthermore, case managers are often limited in their knowledge about the patient’s job requirements and access to the employer and require extra time to build a conversation between the patient and employer without the appropriate resources.

SOLUTIONS

The final question in each session focused on what case managers would change if they had a magic wand at work. Each idea focused on information exchanges:

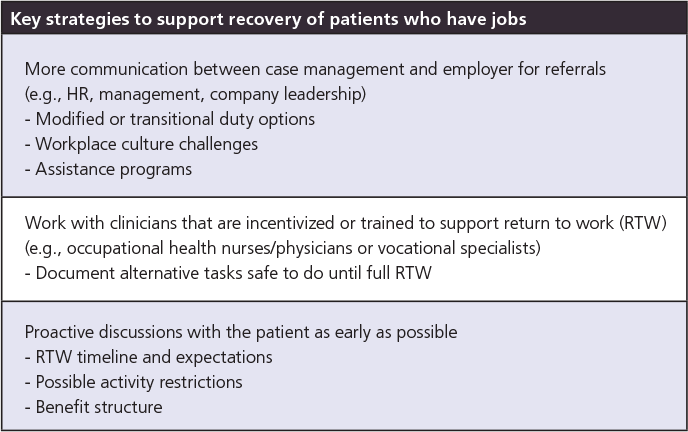

- communication between case management and employers, especially about establishing modified/transitional duty options and how to overcome workplace culture challenges

- working with clinicians that focus on supporting return to activity and can document alternative strategies until full recovery

- proactive discussions with the patients to establish RTW expectations, possible activity restrictions and to outline their health benefits

DUPLICATE OUR STUDY

Want to conduct a study like this at your organization? We started with leadership buy-in, discussing why this research was needed and how we could apply the results to help our front-line case managers. We also asked leadership to recommend experienced case managers who would be interested in participating. Simultaneously, we also had a grassroots effort where we asked colleagues to participate and recommend three others we could contact. In the end we invited 26 internal, experienced case managers, including those who handled short-term disability and/or long-term disability, and registered nurses, to participate in a 30-minute focus group. Out of these, 17 agreed to participate, and 11 attended one of the three sessions conducted in the spring of 2023.

We then narrowed our discussion to only three questions: critical turning points that can identify complex cases, major themes differentiating complex versus simple claims and tips for how to prevent or mitigate these factors. Our researchers prompted the questions and summarized some of what participants said during the sessions, but mostly let the discussion occur naturally.

Our participants had between 5 and 15+ years of experience, were predominantly women and participated via a virtual video call. These three focus groups were lively discussions, and while each group touched on different topics, our analysis was able to pull out the three major “red flag” themes.

REFERENCES

Hogh, A, & Viitasara, E. (2005). A systematic review of longitudinal studies of nonfatal workplace violence. Euro J of Work and Organiz Psych, 14(3), 291-313.

Shafi, R, Smith, P, & Colantonio, A. (2019). Assault predicts time away from work after claims for work-related mild TBI. Occu Environ Med, 76(7), 471-478.

Wizner, K, Harrell, M, Berenji, M, Gaspar, F, & Christian, J. (2021). Managing work disability to help patients return to the job. J Family Practice, 70(6), 264-269.