Long‑Term Care’s Staffing Crunch

Why hiring and keeping caregivers is the defining challenge for nursing homes, assisted living, and home care—and what can move the needle.

BY PAUL BORJA, PhD, DNP, EdD, MBA, PHN, RN, CCM, ACM-RN, CMAC, CMGT-BC, CNML, CMCN, FACDONA, FAACM

The problem isn’t just “not enough people.” It’s a system that churns them out.

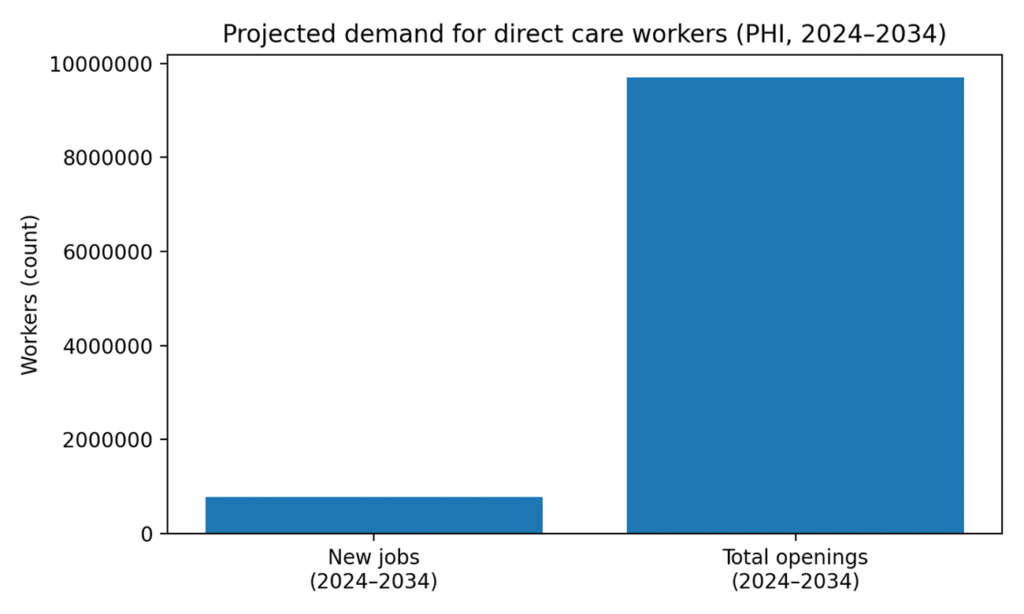

Across the U.S., long‑term care (LTC) providers—skilled nursing facilities, assisted living communities, and home‑ and community‑based services—are running into the same wall: demand for care is rising faster than the workforce that delivers it. PHI projects the direct care workforce will need to fill about 9.7 million openings from 2024 to 2034, including roughly 772,000 new jobs created by growth alone. At the same time, wages remain modest in many roles that require physically taxing work, emotional labor, and high accountability.

“Long‑term care runs on relationships. Turnover breaks them.”

The staffing story is often framed as a short‑term shortage. In reality, it is a long‑term retention challenge driven by pay compression, burnout, limited career ladders, and reimbursement models—especially Medicaid—that often don’t keep pace with labor costs.

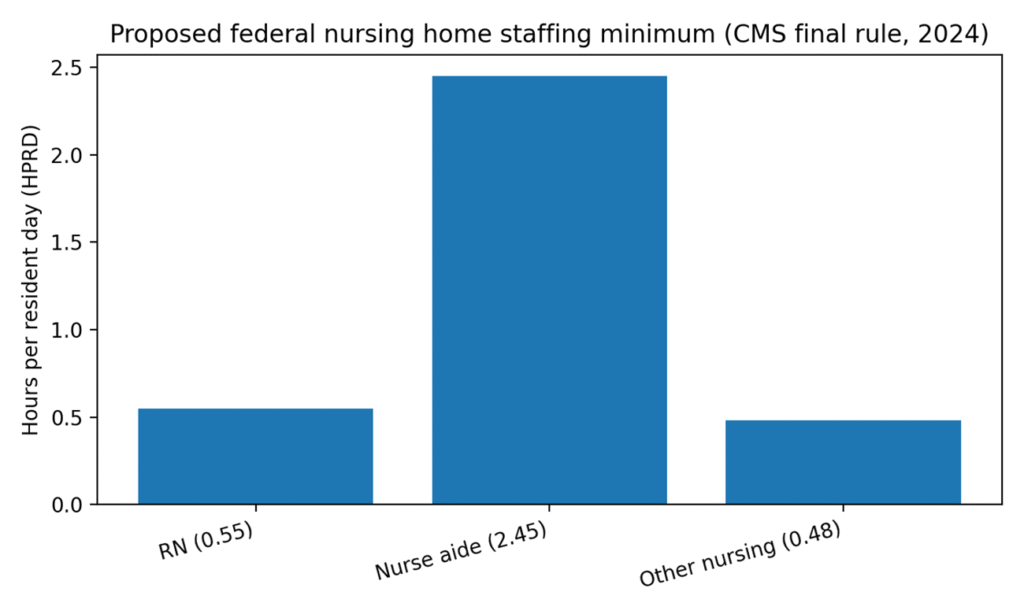

What “adequate staffing” looks like—and why it’s contested

Staffing standards are frequently expressed as hours per resident day (HPRD) in nursing homes. In April 2024, CMS finalized minimum staffing standards that would have required 3.48 total nursing HPRD (including 0.55 RN HPRD and 2.45 nurse aide HPRD, with the remaining 0.48 flexible across nursing roles). The policy became a flashpoint: advocates argued it would reduce preventable harms, while operators warned they could not hire to the mandate. By late 2025, CMS moved to rescind the minimum staffing requirements, underscoring the volatility of the policy environment.

Figure 1. Composition of the 2024 CMS staffing minimum (HPRD).

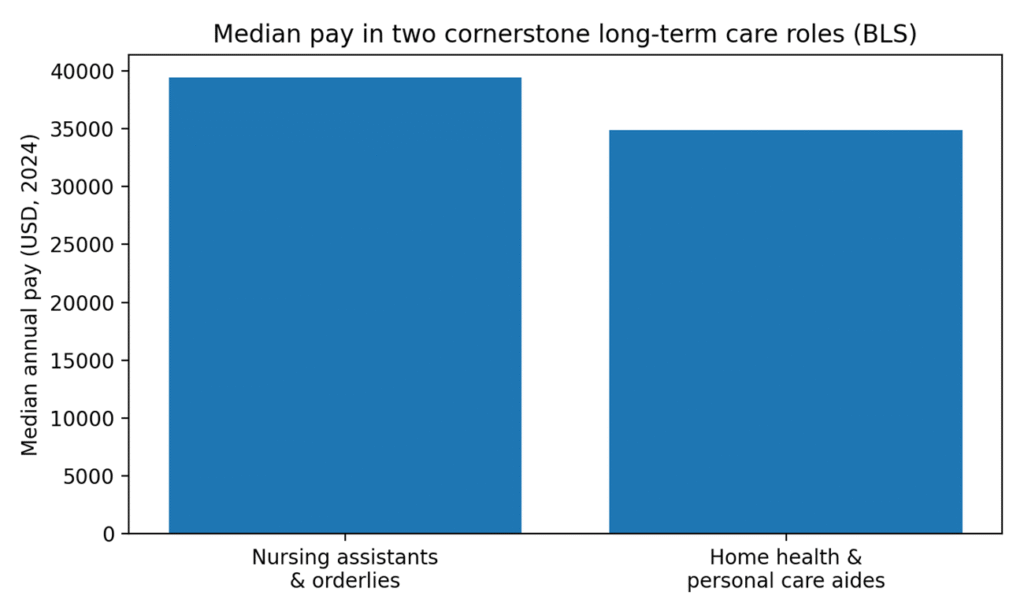

The labor-market math: high demand, low margins

Direct care is among the fastest‑growing job categories in the U.S., and the scale of replacement needs is enormous. PHI estimates 9.7 million total openings in direct care from 2024–2034 when separations and occupational transfers are included. Yet median pay remains relatively low: BLS reports 2024 median pay of $39,430 for nursing assistants and orderlies, and $34,900 for home health and personal care aides.

Figure 2. Median annual pay in two core LTC occupations (BLS, 2024)

Figure 3. Projected demand for direct care workers (PHI, 2024–2034).

Figure 3. Projected demand for direct care workers (PHI, 2024–2034).

Why staffing breaks down: five recurring pressure points

- Pay and benefits lag competing sectors: When retail, warehousing, or hospitality offer comparable wages with less physical strain, LTC loses candidates—especially for entry roles.

- Burnout, injuries, and moral distress: Short staffing increases workload and overtime, raising injury risk and accelerating burnout. Burnout then feeds turnover—creating a self‑reinforcing cycle.

- Acuity rises while staffing stays flat: Residents and clients often have more complex needs than in prior decades, but staffing models and care processes haven’t always evolved accordingly.

- Agency dependence and cost volatility: When facilities can’t fill shifts, they may rely on contracted staff. GAO documents how demand for supplemental nurses increased during the pandemic era, adding cost pressure for providers already operating on thin margins.

- Training bottlenecks and career ladders: From limited clinical preceptors to scarce advancement pathways, workers may not see a long‑term future in the field—even when they love the mission.

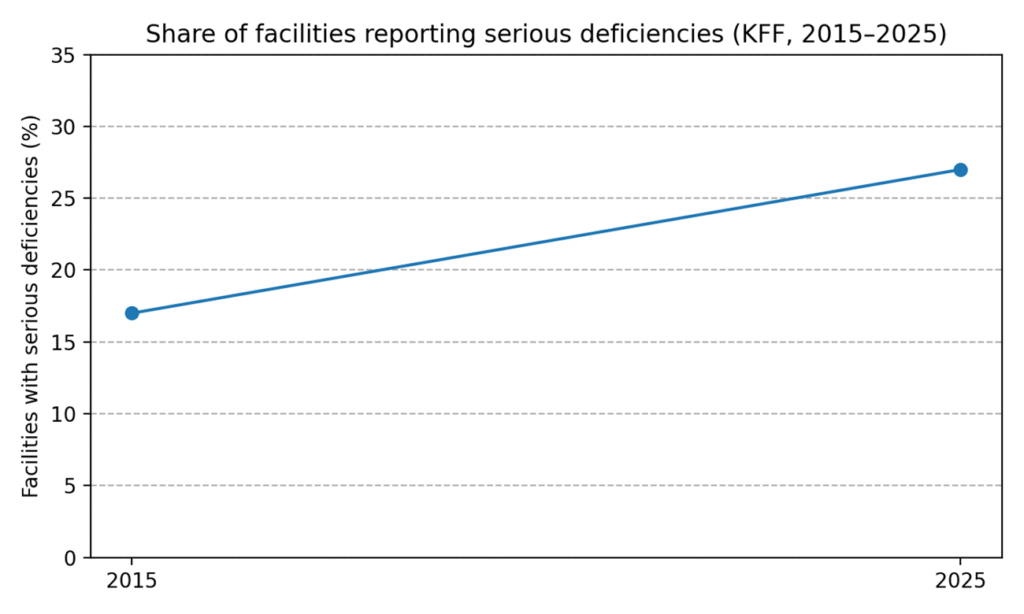

What it means for quality and safety

Decades of research links staffing to outcomes, but the practical signal shows up in daily operations: missed care, delayed response times, and instability. KFF’s analysis of certified nursing facilities finds the share reporting serious deficiencies rose from 17% in 2015 to 27% in 2025—an ecosystem signal that oversight concerns are growing even as providers struggle to recruit.

Figure 4. Serious deficiencies increased over the past decade (KFF, 2015–2025).

Figure 4. Serious deficiencies increased over the past decade (KFF, 2015–2025).

What helps: practical fixes with evidence behind them

- Stabilize schedules: Self‑scheduling, consistent assignments, and limiting mandatory overtime improve retention by restoring predictability and relationships.

- Pay differently—not just more: Wage increases matter but so do benefits that reduce financial stress: paid leave, childcare supports, transportation assistance, and tuition pathways.

- Build internal float pools: Creating in‑house staffing pools can reduce reliance on agency staff while offering flexibility to employees.

- Grow your own talent: Partnerships with community colleges, on‑site CNA training, and apprenticeship models shorten time‑to‑hire and improve fit.

- Redesign care delivery: Team‑based models that fully use LPNs/LVNs, medication aides (where allowed), and technology for documentation can free RNs for assessment and supervision.

- Focus on the first 90 days: Structured onboarding, precepting, and early check‑ins target the window when most churn occurs.

Questions boards and administrators should be asking:

- What is our 12‑month turnover by role (CNA, LPN/LVN, RN)?

- How many shifts per month are filled by agency staff—and at what premium?

- Do we have consistent assignment for residents/clients who want it?

- Are wage bands compressed (new hires making near‑tenured staff)?

- What percent of call‑outs are driven by childcare/transportation barriers?

- Are supervisors trained for coaching—not just compliance?

Bottom line

Long‑term care staffing challenges won’t be solved by a single mandate or one‑time bonus. The facilities that stabilize their workforce tend to do the basics well—predictable schedules, fair compensation, strong onboarding, and a culture that treats direct care as skilled work. The bigger policy question is whether the payment and regulatory environment will support those investments consistently enough to make them stick.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). “Minimum Staffing Standards for Long‑Term Care Facilities.” Fact Sheet, Apr. 22, 2024.

- Federal Register. “Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Repeal of Minimum Staffing Standards for Long‑Term Care Facilities.” 3, 2025.

- “Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts 2025.” Sep. 15, 2025.

- “Understanding the Direct Care Workforce: Key Facts & FAQ.” Accessed 2026.

- S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Occupational Outlook Handbook: “Nursing Assistants and Orderlies.” (2024 median pay).

- S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Occupational Outlook Handbook: “Home Health and Personal Care Aides.” (May 2024 median pay; 2024–2034 outlook).

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). “A Look at Nursing Facility Characteristics in 2025.” Dec. 17, 2025.

- S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). “Expanded Use of Supplemental Nurses during the COVID‑19 Pandemic.” GAO‑24‑106447, Aug. 1, 2024.

- “Judge blocks Biden rule requiring more staff at nursing homes.” Apr. 8, 2025.

Paul Borja, PhD, DNP, EdD, MBA, PHN, RN, CCM, ACM-RN, CMAC, CMGT-BC, CNML, CMCN, FACDONA, FAACM, is very passionate about education, health equity, and focus on social determinants of health. He has been in the healthcare industry for 18+ years as a nurse, educator, case manager and leader in different facets. Paul has always sought for opportunities to serve his community and the profession he is in. Paul looks forward to giving more of his time and expertise to important causes. He is a multi-site director for Adventist Health Lodi Memorial and Dameron Hospitals and an adjunct professor of administration and management at California Coast University. He was a recipient of the Kaiser Permanente Continuity of Care Excellence Award in 2017 and 2018. He had recently been featured by Aidin for their #CMSpotlightAward. He is currently the CMSA National Board Secretary and the president of CMSA Sacramento Chapter. He is a Fellow for the American Academy of Case Management and Fellow of the Association of Certified Directors of Nursing Administration.

Paul Borja, PhD, DNP, EdD, MBA, PHN, RN, CCM, ACM-RN, CMAC, CMGT-BC, CNML, CMCN, FACDONA, FAACM, is very passionate about education, health equity, and focus on social determinants of health. He has been in the healthcare industry for 18+ years as a nurse, educator, case manager and leader in different facets. Paul has always sought for opportunities to serve his community and the profession he is in. Paul looks forward to giving more of his time and expertise to important causes. He is a multi-site director for Adventist Health Lodi Memorial and Dameron Hospitals and an adjunct professor of administration and management at California Coast University. He was a recipient of the Kaiser Permanente Continuity of Care Excellence Award in 2017 and 2018. He had recently been featured by Aidin for their #CMSpotlightAward. He is currently the CMSA National Board Secretary and the president of CMSA Sacramento Chapter. He is a Fellow for the American Academy of Case Management and Fellow of the Association of Certified Directors of Nursing Administration.