BY , MD, MPH, , DO, AND , PhD

BACKGROUND

Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infection is the number one cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea. Additionally, it is increasingly a cause of gastrointestinal illness in the community, with more than one-third of all U.S. infections occurring outside the hospital setting. There are approximately 450,000 cases of C. difficile infection (CDI) each year in the United States. Recurrence of CDI is a significant problem, with a cycle of multiple recurrences in a single patient contributing to the complexity of care. In patients treated for an initial episode of CDI, recurrence can occur in up to 35%, and in patients having three or more episodes, the rate increases to 40-65%.1

Signs and symptoms of CDI include watery diarrhea up to 10 times per day, abdominal pain and distension, fever, loss of appetite, swollen abdomen and dehydration leading to possible kidney dysfunction. Persistence of CDI can lead to sepsis, admission to the intensive care unit and toxic megacolon that may require surgical intervention.2 The impact of CDI on a patient’s quality of life cannot be overstated. There are significant physical and psychosocial consequences such as hesitancy to return to normal activities of daily life due to post-CDI symptoms after eradication of the infection and fear of a recurrence. Around 40% of patients believe that their symptoms will never resolve.3

Patients with active disease or those suspected of having CDI will receive treatment, and their care will be managed across multiple healthcare settings involving a variety of healthcare workers. Within these settings, it is essential to understand how awareness of all aspects of this infection is needed to optimize patient care. Case managers can play a key role in this continuum of care to help reduce infection recurrence and direct those with recurrent C. difficile (rCDI) to the most appropriate healthcare provider. Implementing a well-structured transition of care (ToC) process can ease the burden on the healthcare system, patients and their families, resulting in improved outcomes.4

IDENTIFY PATIENTS WITH CDI RECURRENCE DURING TRANSITION OF CARE

CDI can present with a variety of signs and symptoms, so it is important for the patient and caregiver to be aware that the disease can recur and inform medical staff of prior infections. Upon a recurrence, some patients will not return to their primary care provider or even to the same hospital, so the burden is on the patient to provide their history of prior infection(s). A key component of the ToC process involves a focus on medication management, which is known to improve health outcomes. On an ongoing basis, it is essential to reconcile discrepancies in medication therapy that will translate into improved outcomes and reduced readmissions. Accurate and timely communication is a vital part of this care transition. Data shows that initiation of these transition of care programs can improve communication between clinicians, pharmacists and caregivers. Based on CDI patients’ journeys and the course and recurrent nature of the infection, it is clear that a carefully planned CDI ToC process would help improve outcomes in these patients.5 Thus, the role of the case manager is vitally important to ensure a seamless care transitions workflow to make real positive impact.

KEY COMPONENTS—EDUCATION OF PATIENTS BASED ON THEIR CURRENT CDI DISEASE JOURNEY

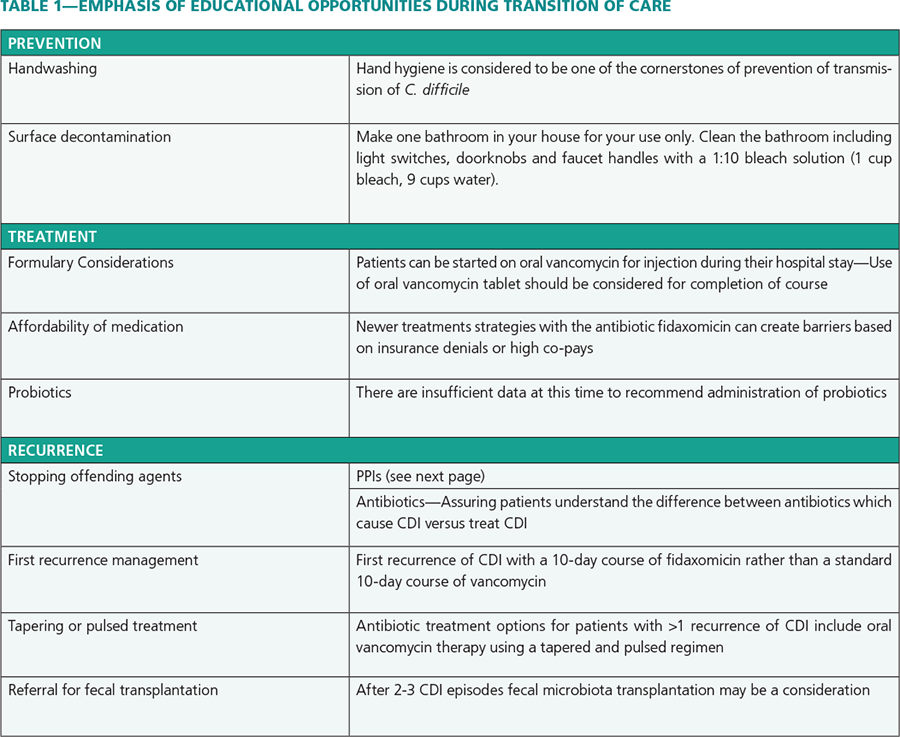

Three main topics are critical to the ToC process for case managers: education, communication and collaboration and outcome follow-up. Primarily, patient or caregiver education on C. difficile prevention, treatment and recurrence is paramount. Individual assessment of each patient’s and caregiver’s understanding should be assessed during counseling. It is essential to ensure that the patient and their caregiver understand the importance of handwashing and overall hygiene and what to do in the event of a recurrence. Second, communication and collaboration among providers with respect to medications should occur with an emphasis on inpatient and outpatient pharmacists. Completion of treatment in accordance with established guidelines and any obstacles such as insurance denials/co-pays must be addressed before discharge in order to ensure patient compliance as well as stopping other medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Finally, patients’ outcomes need to be tracked to monitor for recurrence and to recommend or refer patients for management.5

Note. From “Transitions of Care in Patients with Recurrent C.Diff: An Opportunity for Collaboration Among Community Health System Pharmacists,” by S. Panella and G.S. Tillotson, May 2021, Pharmacy Times, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/transitions-of-care-in-patients-with-recurrent-c-diff-an-opportunity-for-collaboration-among-community-health-system-pharmacists. Copyright 2021 by Pharmacy Times. Used with permission.

Frequently, healthcare-acquired CDI patients are discharged into the home environment or are followed loosely by transitional care services.6 This makes communication and education around the day of discharge especially important. In electronic medical record systems, the patient’s primary pharmacy is listed so contact information is readily available for the inpatient or ToC managers to inform the outpatient pharmacist. It has been suggested that a pharmacist discharge care plan will facilitate the coordination of medication management between the hospital and outpatient pharmacist, resulting in continuity of care and access to updated patient information.7

Important to management of CDI is educating the patient on the impact of recurrence. One critical question to discuss during medication counseling that can assess a patient’s understanding could be: “Who would you call if you have diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain or vomiting that gets worse after you finish your antibiotics?” A patient’s response to this question would demonstrate what level of understanding they have and what actions they need to take at the first sign of recurrence. Ensuring patients know what symptoms to watch for and what to do if they occur will allow for earlier intervention before patients become dehydrated and too weak to be managed at home.5 Provision of educational material in different languages is very helpful. A “traffic light” system of symptoms is also useful to help the patient understand what to do at which stage.

Miller and Schaper found that uncoordinated transitions from the inpatient setting to the home environment created hardships for patients and families when a readmission occurred as a result of failed inpatient discharge processes. The authors noted that complications that arose post-discharge were often preventable based on appropriate discharge education during the initial hospitalization.8

Pharmacists should also be made keenly aware of other medications that may put patients at risk for infection recurrence. Continuous use of PPIs has been independently associated with a 50% increased risk for recurrence of CDI in a retrospective review. Surprisingly, re-exposure to antibiotics was associated with only a 30% increased risk.9

In conclusion, case managers can play a critical role in the ToC for patients with CDI. Overall, transitions of care should focus on educating the patient about their condition and enhance the collaboration of providers and pharmacists to optimize patient outcomes. All practitioners involved in the patient’s care have a responsibility of ensuring proper management and prevention/management of recurrence.