Sales Skills: A Method To Improve Communication And Patient Satisfaction

Sales skills provide an additional skill set for case managers and others in healthcare to improve both communication and patient satisfaction. To some readers this may sound like heresy! How in the world would learning about sales help? Just the term sales can create a sense of negativity, certainly not a helpful tool. This article will provide you with a deeper understanding of sales and how these skills will assist you with patients, families and your co-workers.

Do you typically think of sales as those people who pressure you into something you really don’t want? Or do you see salespeople as those who can help you fill a need? When you find a salesperson helping you solve a need, you begin to feel “listened to,” “helped” and on the road to a solution. As case managers you do the following:

- Communicate

- Provide information

- Assist patients to learn what is needed to be healthy

WHY?

“Patients who understand the nature of their illness and its treatment, and who believe the provider is concerned about their well-being, show greater satisfaction with the care received and are more likely to comply with treatment regimes” (deNegri, et al).

This is a good way to see the connection between sales and healthcare. It is really all about good communication. If we are good salespeople, we are trying to solve a problem. If we are good healthcare providers, we are trying to help achieve a good outcome.

SALES — WHAT DOES IT REALLY MEAN?

In its most basic definition, “sales” is just an exchange of a product or service for compensation. The important piece is the VALUE of that product or service. That VALUE is really determined by the customer — is this product worth the money? Worth the resources and effort? And is it important to me? It is imperative that the seller identify the VALUE for the customer to make a good decision. There are skills that the seller needs that are both proven effective and expected by customers.

SALES SKILLS

From the customer’s viewpoint, we expect all these skills from any salesperson that we deal with. Are they listening to what I am saying? And we expect them to be the expert in whatever the product is — or at least to be able to get the answers easily. How many times have you thought to yourself about a salesperson, “She’s not hearing me!”? When the transaction is going well, we as customers will feel listened to, taken care of and happy with the purchase.

SKILLS AND PROCESS

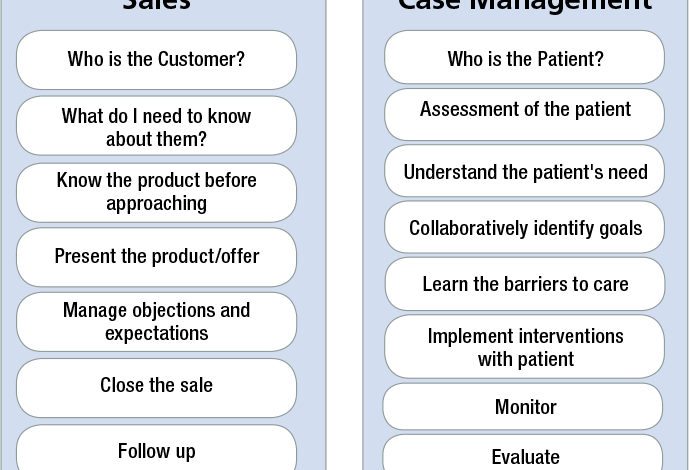

When exploring the process of a sale, one can make the comparison to the case management process. Here is a comparison:

In the comparison the WHO is identification of a client/customer and a patient. Regardless of setting in sales there is targeting to find the right customer for a product. This can be done via advertising or exploring for a decision maker. In case management (CM), accrediting bodies will examine how patients are identified. In managed care, CM patients may be identified through diseases or dollars spent per case. In direct care settings the identification may again be by condition, or by setting.

Knowing the product. As customers we expect the salesperson to thoroughly know the product. How does it work? Do I need additional materials for it to work, etc. Our patients also expect case managers to know everything — what is the diagnosis; what does it mean; why a certain test; and what will I do once I leave the hospital?

Just as it is important for a salesperson to know what they are selling, a CM must be prepared by first knowing the patient. If the patient’s condition is not familiar, then we must know where to get strong evidence-based information. In other words: read the chart, know your patient before any conversation, know the purpose of the interaction and be prepared by learning about conditions you are not familiar with.

Complete the assessment or take time to read through one that has been completed. What are you learning from the assessment questions? Are goals easily identified? What interventions should be established, or what does this patient need in order to reach their goals? This takes time because it must include and respect the patient’s goals and perspective. In the same manner, a salesperson will want to explore a customer’s needs. What are their pain points? What is it the customer needs and that the salesperson can provide? What steps will be required in order to complete a sale?

During prospecting for a sale (a case), during the assessment of a patient, inevitably there will be barriers. Proper preparation allows you to understand the potential barriers and establish a plan to approach each one.

In sales the frequent barriers prior to closing a sale are:

- Cost

- Product does not meet a need

- Feeling pressured to make decision or

- Need approval of another party (spouse, partner, decision maker).

Are you now thinking of the similar barriers encountered with a patient to achieve a goal or follow a plan of care? Many barriers fall into the same patterns:

- Cost

- Plan does not meet their understanding of the need

- Feeling pressured to make a change or

- Does not agree with plan (diet; meds; lifestyle).

The challenge is always to identify the actual barrier, which may mean further assessment and exploration in order to move to the next step.

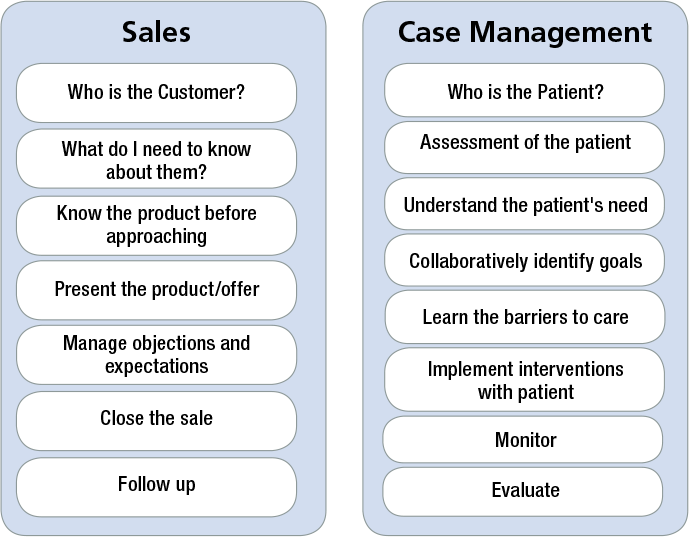

EMOTIONS

Decisions are typically not cut and dry, or done in a vacuum. Emotions play a role in understanding the value of a product or healthcare decision.

Emotions enter into both sales and CM functions and roles, either from the patient or client’s viewpoint or the CM or salesperson. Think of your emotion at the time of an interaction. Are you asking a co-worker to work late or informing a patient they cannot be discharged yet, which may cause you to become fearful? Or you are the co-worker asked to stay late, and you are angry because you really want to go home?

Assumptions — the offhand remark at report about a disagreeable patient can impact your interactions. You go to buy a car and just assume the salesperson is going to pressure you into a purchase.

Just knowing and understanding the human emotions tied to an activity can give you pause, long enough to re-adjust and prepare. The pleasure emotion is the patient is feeling better, ready for discharge and fully understands their role in staying healthy. There can be pleasure in many interactions once a relationship of trust is built, which is true for all included.

EXPECTATIONS

Considering two of the emotions involved in the sales process: assumptions and anger; you can easily add disappointment. Regardless of the product and setting both the “seller” and “customer” will naturally have expectations of a transaction. Consider someone is scheduled for a medical test at a particular time. A typical expectation is that the test will begin at that specific time. Often (we all know this) the test is delayed and now the person’s anxiety increases and there are stirrings of anger beginning. This happened to me recently, and my expectations were re-set by the technician who was conducting the test. She listened to my concerns, gave the rationale and details of the delay and what exactly would occur. Throughout the testing process, she continually explained the next steps and details. Not only did my frustration quickly dissipate, I then understood the “why” and that really provided a satisfactory experience.

The skills employed by this technician were:

- active listening

- provided clarification

- was not defensive or condescending

- detailed next steps

- managed my expectations

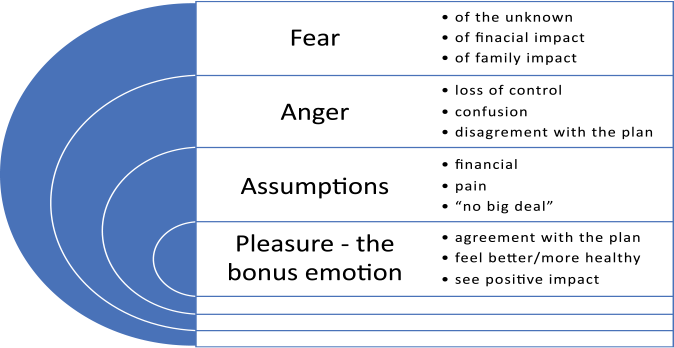

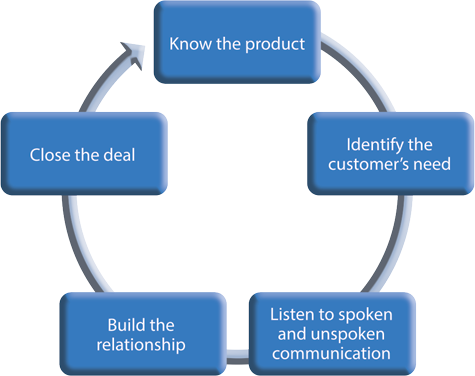

COMMUNICATION

The main connection between sales and healthcare is good communication, which needs to be clear, concise and understood. CMs who are tasked with coordination must employ strong communication skills among the team, patients, families and external referral sources. Accrediting bodies lay out standards that recognize the need for CMs to have the abilities to identify problems, strategize with colleagues and work with patients/families in developing plans of care.

Easy to understand, clear and direct communication not only improves patient satisfaction, it enhances employee satisfaction and minimizes risks. In its simplest definition (thanks to Ms. Google) communication is an exchange of information and a connection between people.

Good communication things to remember:

- It’s not about you

- Focus

- Get to the point

- Be brief

- Pay attention

- How is the listener reacting?

- Listen to the other person

- Wait — until the other person is done (Sunderhaus, 2016).

These few pointers are easy to remember when you think of those things that unnerve you in a conversation.

Effective communication…occurs when the intended meaning of the sender and perceived meaning of the receiver are the same (Univ. of Ulster).

In the end, good sales and good case management come down to basic customer service. Good service builds relationship and satisfaction with the transaction of business or healthcare consultation.

Most people want their concerns truly heard. When they feel ignored, dismissed or disregarded, they get mad or madder. However, if you listen hard enough, you might just detect that issue they can’t or don’t want to express, which allows you to offer a solution, or at least buy some time to work with them.

To be truly empathic, one requires the ability to set aside personal perception, assumptions and bias, and focus on the customer. This is particularly hard with a difficult or unpleasant patient, but that is precisely when the technique yields the biggest dividends. By truly hearing them, you can offer concrete solutions that are likely to satisfy. Frequently, when patients are upset or stressed by a situation outside their control, the simple act of listening and validating their concerns goes a long way to providing the required service. You can help them to feel calmer and reassured, even if all you can provide is a reflection of their concern and a statement that you will do all in your power — limited though it may be — to correct or improve the situation.

Ask yourself, “Why is this person so difficult? Are they frightened for themself or a loved one? Are they frustrated by their inability to make things better on their own?” They can frequently be calmed by expressions of concern that validate their fears but suggest that there is help available, even if it is not exactly what they have requested at that moment. So easy to say, but how do you do it? Here are six tips:

1) ASK LEADING QUESTIONS AND LISTEN CAREFULLY TO THE ANSWERS.

Don’t allow yourself to think about anything other than what the patient is telling you in response to your questions. Ask questions like:

- What has happened to make you feel that way?

- How did this situation occur?

- When did the problem begin?

By understanding the patient’s perspective, you may:

- Identify misperceptions on their part and offer an explanation that allows you to reset their expectations.

- Learn that your understanding of the situation is incorrect and caused you to offer inadequate or the wrong support.

- Discover a way that you or a part of your team has failed to follow through or deliver on a promise.

You can offer a clearer explanation or a sincere apology and find a way to correct the problem. When you find the discrepancies, you can manage the problem better and find new resolutions.

2) CHECK YOUR BIASES AND MAKE SURE NOT TO LET THEM SHOW

One day I was working a flight from Chicago to Los Angeles when Clint Eastwood boarded the flight with a large entourage. It was one of those big aircraft where you board in the middle of the plane and first-class customers get to turn left to the quiet comfort of an upscale cabin, while the majority of travelers turn right to go to the confines of economy class. Well, Mr. Eastwood and a beautiful young woman turned left to settle into their first-class seats and the entourage turned right. As a self-righteous young man offended by the misuse of wealth, power and stardom to prey on young women, I commented to my co-worker, “That’s disgusting! That girl is young enough to be his daughter.” One of the straggling entourage overheard me and quietly commented, “She is his daughter.”

Don’t let you bias or opinion or preconceived ideas about the world get in the way of your customer service.

3) PROVIDE HONEST AND DIRECT COMMUNICATION AS PROMISED

Patients want to know what will happen and when. One day I was working a flight from Philadelphia to Chicago when a huge snowstorm hit Chicago. We were delayed on the runway for 4 hours in Philadelphia before we even took off. I told the passengers we would do all in our power to get them safely to Chicago as fast as we could, but I was clear it would take a long time and it would be frustrating day. I also told them I would update them every 30 minutes, even if only to tell them there was nothing new. The crew served drinks and talked to the passengers while we waited. We finally took off for Chicago, and when we arrived in the Chicago airspace, the weather had deteriorated. We circled for as long as our fuel would hold out, but without luck. We had to go to Indianapolis to refuel, and the crew was past our duty day, so the flight canceled in Indianapolis.

Throughout the ordeal, I talked to the passengers frequently and let them know exactly what was happening and what they could expect. As they got off the plane in Indianapolis, 7 hours into what should have been a 90-minute flight, that didn’t arrive at their destination, nearly every passenger thanked me and the crew for our hard work. They knew we had done our best, and we never left them guessing about what was next or lied about things to make it seem better than it was.

4) AVOID THE IMPULSE FOR THE FLIPPANT OR STINGING RETORTS

One day when I was working a flight from Hartford, Connecticut to Chicago, we were delayed by a massive snowstorm that was slowing down O’Hare. The two agents at the gate were overwhelmed with concerned passengers. I stepped off the plane and used a third computer to help answer questions and offer reassurances about missed connections and possible alternative routes for rebooking. I was confronted by an angry businessman with an important meeting in Chicago. He had to get there right now! He was rude, self-important and belligerent. After I explained that the weather was the issue and no one could avoid that, he told me that he was going to our competitor for better service. I immediately responded from my own anger, “You do that sir. I’m sure the weather at that airline is much better than we have today!” It felt good and got a few chuckles from the crowd witnessing his performance but only served to make him angrier. Imagine my chagrin when I learned that the other airline had metered their flights into the O’Hare differently and had chosen to cancel or delay flights from other cities to deal with the weather, but their flight from Hartford went nearly on time.

5) KNOW YOUR LIMITATIONS, BUT DON’T LET THEM PREVENT YOU FROM OFFERING GOOD SERVICE.

When the situation is difficult and upsetting, but there is honestly very little to do to make things better, the most important question is, “What can I do right now that is within my power, to make things better for you?” Frequently, this sincere offer to rectify an impossible situation is enough to allow the customer to calm down and recognize that as frustrating as things are, there really is no way for them to get what they want.

6) KEEP YOUR PROMISES — AND COROLLARY — UNDER-PROMISE AND OVER-DELIVER

One of the most important aspects of good service is making certain the only surprise is a pleasantly better experience than expected. When our clients are in need, they are normally in an unfamiliar situation, don’t speak “medical” and are frightened that a bad situation is only going to get worse. One of our powers is that we are the people who will sort it out and hopefully make it better. Our work provides a powerful support and reassurance, but only if we do what we say we will do. If you tell someone they will hear from you again in a certain period, they need to hear from you again within the promised time, even if is only to tell them we are still working to resolve the issue (see 3 above). When you make a promise to get back to someone, add a little extra time for wiggle room and to build in the chance to do better than promised. Make sure the details of the support you offer are realistic, and then work to surpass the offer. Finally, clearly communicate all your promises to the interprofessional team, so they can follow through with their part, and only make commitments you know they can keep.

Sales and the work of case management is an interaction among people, and that interaction is most valuable when the recipient of our service feels that we care about them and are listening to their needs. There is nothing more satisfying than being heard and understood, and if you listen empathically, you can deliver that kind of service. In the end, it is our patients’ understanding that we care, hear and value them that help us to provide them with successful guidance through their illness, or disease.

REFERENCES

Connie Sunderhaus RN-BC, C. (2016). Be Compelling! Communication for the Case Manager. CCMC New World Symposium2016. CCMC.

deNegri, B. e. (n.d.). Improving Interpersonal Communication Between Health Care Providers and Clients. Quality Improvement Project. Retrieved from www.urc-chs.com

Golkar, G. (2016, March 30). 7 Rules for Effective Customer Service Communication. Customer Service. Retrieved from https://www.vocalcom.com/en/blog/customerservice/7-rules-for-effective-customer-service-communication/

https://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/healthbasics/WhatIsHC.html. (n.d.). Retrieved from Health Communication.

Lauer, C. (2013, June 25). Teaching Doctors How to Sell. Retrieved 2019, from Becker’s Hospital Review: https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physicianrelationships/teaching-doctors-how-to-sell.html

Ripp, C. B. (2018). Trust me, I’m a physicia using sales skills:….. HEALTH MARKETING QUARTERLY, 35(4), 245-265. Retrieved Dec 2019, from https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2018.1524594

Tara Dixon, M. O. (n.d.). Communication Skills. Making Practice Based Learning Work project, University of Ulster. Retrieved 2016, 2020, from http://cw.routledge.com/textbooks/9780415537902/data/learning/11_Communication%20Skills.pdf

Vermeir P, V. D. (2015, Nov). Communication in Healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 69(11), 1257-67. doi:doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12686. Epub 2015 Jul 6