Suicide Prevention in Teens and Children

BY AND

On October 19, 2021, faced with the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on an already strained pediatric mental health system, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Children’s Hospital Association declared a “national emergency in children’s mental health.”1 The pandemic is unlike any event in recent history, and children growing up during this time face isolation, trauma, depression, anxiety and grief. This has been seen through increased access to mental healthcare during the pandemic. In a study by Leeb et al, children had a significant increase in psychiatric visits to the ED compared to prior to the pandemic. For kids aged 5-11, visits were up 24%. For older children from 12-17, mental health emergency visits were up by 31%.2 For some children, options for mental healthcare can be extremely limited due to the demand for quality services overwhelming the capacity of child psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, school counselors, and other mental healthcare clinicians. It is unclear if the current labor shortage in the U.S has had any effect on the mental health workforce, ultimately making access to care more difficult.

Of course, the most extreme and life-threatening mental health emergency is a suicide attempt. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) supplies sobering data on suicides in the United States. The rate of suicide has increased 33% from 1999 to 2019, with a small drop in 2019. More than 47,500 people died by suicide in 2019, which was one death every 11 minutes. Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death for all ages.3

Unfortunately, children are not immune from suicidal thoughts and behaviors, as suicide is the second leading cause of death for people aged 10-34.3 Through the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System data, we know that 18.8% of teens surveyed considered suicide in the preceding 12 months, with 15.7% having a suicide plan; 8.9% of teens surveyed had a prior suicide attempt, with 2.5% reporting that they needed medical care due to an attempt.4

Some groups of children and adolescents are at even higher risk. For example, the suicide death rate among African American youth aged 5 to 14 years is increasing more than any other racial or ethnic group.5 Youth who identify as sexual minorities or LGBTQ+ are three times more likely to try suicide when compared to their peers who identify as heterosexual.6

Even children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, such as autism, are at risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. In one study, up to 11% of children with autism spectrum disorder were noted to have suicidal thoughts.7 Even young kids between the ages of 5-14 years with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), so common in the pediatric population, are at higher risk for suicide death when compared to teens.8 This is due to increased impulsive behavior in children with ADHD. Fortunately, this risk can be decreased by proper treatment of ADHD.9

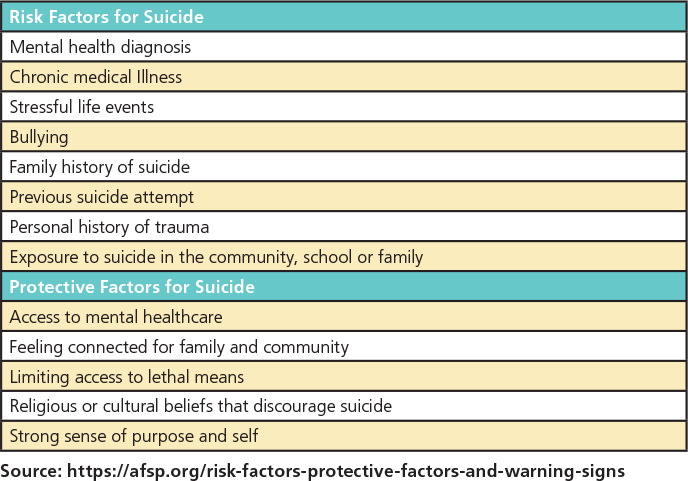

What are some of the risk factors and protective factors for children and adolescents for suicide? From the individual child’s perspective, having a family member who died from suicide increases the risk for suicide. Having a mental health diagnosis (such as depression or anxiety) or a chronic health condition can increase risk as well. Kids with substance abuse problems or with chronic pain are at particular risk. When difficult life situations occur, such as a relationship breaking up or going to a new school, kids can also have an increased risk. The same is true for a personal history of trauma, such as exposure to violence. Children who are bullied can have increased risk as well. Unfortunately, bullying often happens to children who are seen as “different” from their peers, whether it is due to a neuro-developmental disorder, such as autism, or if they are LGBTQ+. Exposure to suicide through media outlets can also increase risk. Sometimes this results in a cluster of suicides in a community. This is referred to “suicide contagion.” It is vital for media, schools and families to address suicide in a suitable manner to avoid triggering “copycat” suicides. Perhaps the most important risk factor for suicide is a prior attempt. Those who have attempted suicide previously are at the highest risk of trying again. It is important to understand that an attempt that may seem insignificant to an adult may be a sign that other attempts will follow and may have tragic consequences.10

What are some factors that can help protect children and adolescents from suicide? Ensuring children and adolescents who are at risk for suicide, due to all the factors previously discussed, have access to mental healthcare is paramount. Keeping kids safe by limiting access to firearms, drugs and other things that they can use to harm themselves is also vital. Ensuring that kids feel connected to family, friends and their community can also develop the sense of purpose and self that is protective. Finally, belonging to a community or having a belief system that discourages suicide can also affect suicidal thoughts and behaviors.10

What can we do to prevent suicide in children? Research has shown that most children who die by suicide have contact with a healthcare provider in the months preceding their death.11 Suicide risk screening can help identify children and adolescents who are thinking about suicide, including those who have an active suicide plan. It is a crucial tool to prevent tragedy. The American Academy of Pediatrics,12 The Joint Commission,13 and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry14 all encourage the use of suicide risk screenings for youth.

Screening can also find those who have had prior attempts, even if parents may not be aware of those attempts. By identifying those at risk, the hope is that those children and teens can be directed to the care they need. Reassuringly, research has shown that asking kids about suicide does not lead to children having suicidal thoughts.15 Often kids who are asked in screening are relieved that someone is reaching out and cares about them. This is the first step to connecting youth with the mental healthcare they need.

School is a place where our children spend so much time and is like a second home. Teachers, school administrators and school counselors can also have a significant role in suicide prevention. Some studies have shown that individuals at risk can be found through screening in the school setting.16 Some data suggest prevention of suicidal thoughts and behaviors is also possible in school settings.17 Of course, appropriate training and education is needed to help children in need of intervention.

Lastly, family support to individuals with suicidal ideation is paramount. Educating parents to recognize signs of suicidal thoughts and behaviors can help prevent tragic outcomes, as can increasing awareness that even kids who are thought to be unable to contemplate suicide can, in fact, have those thoughts. This is often a vital first step for families. Once a child or adolescent is identified, facilitating access to care is important as well as family engagement in treatment teams and participation in family-focused interventions when indicated.18

Children and teenagers do not exist in a vacuum; they are part of a larger community that encompasses family, peers, school, cultural influences, mental health groups, medical practitioners and countless child-serving agencies. It is the integration of these systems that is pivotal as a therapeutic approach. Each adds a layer of protective factors to an individual’s clinical presentation and may influence a positive outcome.19

It does take a village.20

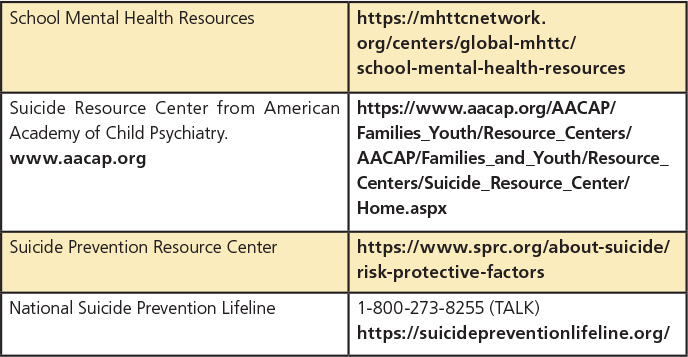

RESOURCES