“I tell all my patients how to do selfcare. It’s up to them whether they adhere or not.”

This is the equality approach to patient education: Everyone gets the same instructions. More literate patients are likely to succeed. But patients with health literacy deficits are not. To achieve equity – that is, to have substantially equivalent outcomes for high and low literacy patients – educational approaches must be different.

The good news is, investing in equitable materials development pays dividends in labor saved as less literate patients independently become as successful as literate ones. Well-developed materials will work as hard as you do.

OVERVIEW

To achieve equity, refocus the goal from “comprehend” to “inspire.” Patient education is for behavior change. Health literacy specialists, however, concentrate on comprehension. The official “Guidelines for Plain Language” (www.plainlanguage.gov), lists 200+ rules, all to improve comprehension.

But comprehension is not enough. Before the pandemic, at one western medical center, despite multiple campaigns for behavior change, doctors’ compliance with hand-washing was only 80%. The doctors did not need greater comprehension. They knew. They did not need to do a return demonstration. They needed inspiration. So the task force had each doctor press a palm into a Petri dish. Photographs of the results were posted as screensavers on computers all over the hospital. Hand-washing shot up to nearly 100%.

Shift from comprehend to inspire in eight steps: Three before you write and five as you write. Only afterward apply as many as you can of the 200 rules of comprehension.

PENPICS STUDIO/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

BEFORE YOU WRITE: Observe, Design, Structure

Step One: OBSERVE

Too often, writers of patient education leap in to tell the patients what they believe patients need to know. But visiting patients in their homes to watch them do self-care reveals false assumptions.

At a university hospital in the Midwest, the readmission rate after prostate surgery was high. Staff blamed the surgeons, nurses, the catheter manufacturer. But the CNO said, “Wait. Let’s have some anthropologists – trained observers – visit patients in their homes and find out what’s really happening.” The observers found that although the instructions for changing day to night drainage bags were clinically correct, patients’ arthritic fingers could not hold two bags and twist a connector simultaneously, the way young nurses could. Patients frequently dropped supplies on the floor. When instructions said “rinse the bag,” patients jammed it up against the faucet for stability. To achieve equity, nurses had to re-think how older patients could succeed. New instructions dropped the rate of infection by 91%.

In another example of missing patients’ real needs, a university hospital in the East listed three FAQs for post cardiac surgery. “When can I go back to work?” “Have sex?” “Drive?” Of course, all three have the same answer: “Ask your doctor.” This is not even satisfying, let alone inspirational. After 300 home visits, anthropologists discovered six questions genuinely on everyone’s mind but not articulated. These questions had answers without consulting a provider. Patients were delighted and relieved. “These nurses really understand me!”

Step Two: DESIGN FOR DISCOVERY

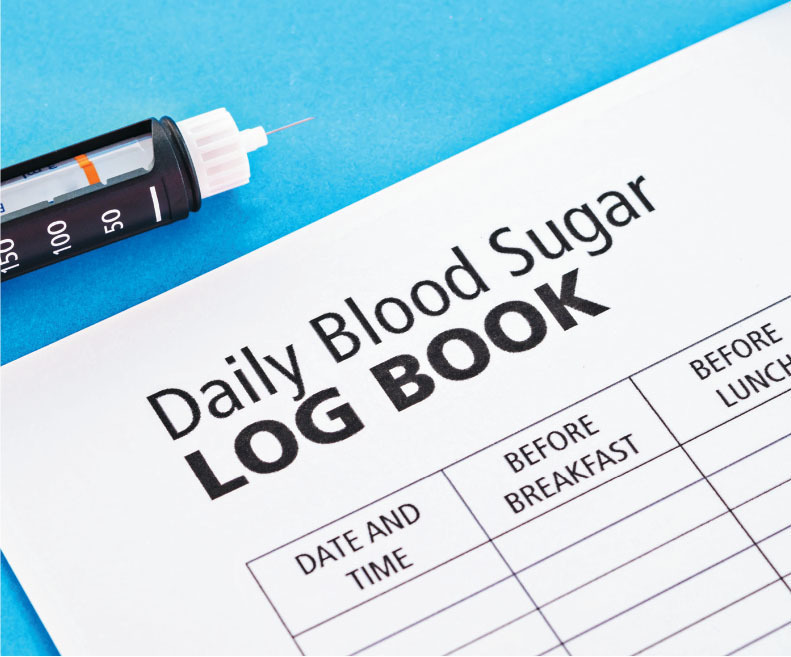

Museums understand discovery learning. They design interactive exhibits to engage their visitors. What could adult patient education do to allow discovery? Consider first how traditional tools for self-care thwart discovery. A traditional diabetes logbook provides a grid for entries. The chart above will appear very familiar, as a similar version is offered by many otherwise highly respected and knowledgeable organizations.

Some patients may succeed with this chart. But low literacy patients won’t easily perceive cause and effect, or trends. For equity, they need a different path to success. A log book that displays exactly the same data but can let patients see at a glance whether they are “in control” and what sends them out of control is more useful. That alternate design could even allow low literacy patients to discover keys to self-management.

Step Three: STRUCTURE BY GOALS, NOT TOPICS.

Professionals learn by topic. When they pass knowledge on, they automatically organize by topic, without realizing different organizing principles are possible.

The American Heart Association has booklets presenting topics (recognize topics by “ing”) Understanding Heart Failure, Managing Heart Failure, Treating Heart Failure, Living Well with Heart Failure. The “ing” turns verbs into nouns. Nouns are static. Verbs are actions, and can also organize material: With heart failure, the goals are to (1) Lighten the load on the heart, (2) Widen the arteries (3) Strengthen the heart muscle.

“Too often, writers of patient education leap in to tell the patients what they believe patients need to know. But visiting patients in their homes to watch them do self-care reveals false assumptions.”

“Providers often forget laughter is the best medicine. You never laugh at a patient, but many experiences with self-care are worth at least a smile. One way to engage a patient in self-care is to let them laugh at small self-care frustrations they hadn’t realized were universal. COVID-19 instructions can say, “Blow your nose before you put your mask on.”

The AHA’s topic approach produces these titles: Treating Heart Failure, Taking Medications, Using Diuretics, plus a list of “Medication Commonly Used to Treat Heart Failure.” Some – though not all – of the medication descriptions include reasons to take these medications at the end. Everything about medications is under one title.

But non-professionals focus on what to do and why. As a section title, Lighten the load covers steps that make it easier for the heart to pump: Take diuretics. Avoid sodium. Limit fluids. Walk to pump blood back up. How to widen arteries is a separate section: Take pills to relax and dilate vessels. Avoid animal fat. Stretch to make the arteries more flexible.

Do you see the difference? Medications are sorted to different sections according to the goal each one achieves. Diet is also divided by goal: Avoid sodium to achieve Goal 1. Avoid animal fat for Goal 2. Walking and stretching are not under a topical heading, “Exercise.” Structuring by goal puts the reasons for self-care steps up front, in the section title, not buried at the end – or forgotten.

Organizing by topic tends to prompt writing sentences that begin “It is important that…” These examples are from AHRQ publications:

It is important that you take your medication as directed and on schedule…

It is very important to take all of your medicine, even if you feel better…

It is important to refill your prescription on time…

Assigning import is a judgment. Imposing judgments on others often arouses resistance. If you organize by goals, the reason for a self-care step is in the title of the section: Its import is obvious.

AS YOU WRITE: Surprise, Amuse, Be Concrete, Relate the New to the Familiar, Illuminate.

Step Four: SURPRISE

The advertising industry adheres to the Four-Second Rule: “If you don’t capture your audience in the first four seconds, they ignore the rest.” Some techniques to capture attention are:

- An unexpected image, title or approach

- Words or images that arouse curiosity

- The beginning of a story

Names like “Healthy Eating” or “Guide to Hypertension” are not unexpected. Photos of generic, smiling people do not arouse curiosity. A list of definitions is not a story. Instead, when visiting patients, note what arouses interest – and what doesn’t. For example, obese people are often bored or even offended by the title “Healthy Eating.” Many believe they know more about healthy eating than providers. Listen to their unexpected description: “I’m a thin person trapped inside a fat body. A diet is ‘getting down to the real me!’” The title of one best-seller self-help book uses surprise to engage people in exercise: “Younger Next Year!”

Step Five: AMUSE

Providers often forget laughter is the best medicine. You never laugh at a patient, but many experiences with self-care are worth at least a smile. One way to engage a patient in self-care is to let them laugh at small self-care frustrations they hadn’t realized were universal. COVID-19 instructions can say, “Blow your nose before you put your mask on.” Instructions on colostomy bags can caution, “Make sure there’s toilet paper on the roll before you start.”

Step Six: BE CONCRETE

Patient education often promises concrete information but doesn’t deliver. Patients want to know, for example, “what’s that pill doing in my body?” But descriptions of how meds work are difficult to find in low literacy. You expect an AHRQ brochure, “Comparing Two Kinds of Blood Pressure Pills: ACEIs and ARBs,” to tell how they’re different. Instead, it only lists how they are the same: “Both do a good job. They work equally well. They have similar costs. The chance of dizziness or headache is about the same.” One health website claims to describe the six categories of diabetes pills, but three have identical definitions. One woman reported she stopped taking her medication because her providers vaguely described a beta-blocker as “for the heart.”

For equity through health literacy, research the mechanism of action for each pill prescribed and write, concretely, how it works.

Step Seven: RELATE THE NEW TO THE FAMILIAR

Patients must remember instructions before they can act. The New York Times ran an article, “An Ancient and Proven Way to Improve Memory,” which stated, “The Rhetorica ad Herennium was written in 80 BC, the first known text on the art of memorization. It teaches that the way to remember a new idea is to associate it with something familiar. We think memorizing is laborious, boring work, because we’ve been taught to do it by rote. These brute-force approaches are dull because they are devoid of any creativity.”

It may seem counter-intuitive that remembering two things is easier than remembering one. Telling a patient that, for example, gout is like a garbage collector who goes on strike or that radiation therapy is basically that same old X-ray you’ve had at the dentist’s office, you’re asking the patient to remember two things instead of one. But think how you remember names at a cocktail party. It’s likely you make up a second item to associate with the name. Two things to remember instead of one.

Step Eight: ILLUMINATE

Most education treats visuals as decoration instead of communication. Simply scattering images can cause serious errors: for example, placing an image of fingernail clippers on a page on foot care.

Decoration misses the opportunity for inspiration. That West Coast task force used images to inspire doctors’ compliance with hand-washing. Images can also inspire patients: A directive to avoid animal fat typically shows an anatomical drawing.

Higher literacy patients may be able to take the drawing seriously and change behavior. Lower literacy levels are less impressed with technical drawings. For equity at low literacy levels, show an image as metaphor.

One patient who had not been inspired by the anatomical drawing responded to the metaphor: “I was going to McDonald’s tonight. I just changed my mind.”

AFTER YOU WRITE

Conventional health literacy rules – ways to increase comprehension – are for polishing content. Only after you follow the eight content steps to create a gem of a patient education piece does the time come to polish your rough draft with those 200 rules on the government webpage “Guidelines for Plain Language Writing.” If you skip the eight steps, you’ll be polishing the wrong rock.

SUMMARY

Equity through health literacy is securing substantially equivalent outcomes in self-care for patients with literacy deficits. Achieve equity by shifting the main goal of patient education from “comprehend” to “inspire.” Eight steps yield success:

Before you write, Observe the Patient, Design for Discovery and Structure by Goals.

As you write, Surprise, Amuse, Be Concrete, Relate the New to the Familiar, Illuminate. After you write, apply https://www.plainlanguage.gov/guidelines/ to enhance comprehension.