BY CAROLE GESCHEIDLE, MSOLQ, BSN, RN, TEENA MANNING, BSN, RN, CCM, AND JULIA MAYER, BSN, RN, CCM

Did you know that to be considered Native American in the United States is a legal/political determination and not simply a matter of racial identity? Also, that this designation has a profound impact on access to and quality of healthcare? If you did not know, you are not alone. Although cultural sensitivity education is now a component of many clinical programs in universities and healthcare systems, little is taught about Native American culture or the health inequities Native Americans face. If discussed, the frame of reference is often from the dominant society’s point of view, not from the lived experiences of Native Americans.

While Native American tribes are not a monolith – there are 574 federally recognized tribes – there are commonly experienced challenges to health and well-being, leading to several health disparities across Native American communities. Many existing health disparities trace their beginnings to historical events that have created generational trauma. An important example of historical trauma stems from the hundreds of thousands of Native American children forcibly removed from their families, homes and cultures to attend government or faith-based boarding schools (1). These institutions tried to transform Native American people into a more Western European culture, causing a loss of traditional language, ceremonial practices, culture and traditions. Many children died due to abuse and untreated illness, and for survivors, many were permanently separated from families unable to find a record of their location. Generations of surviving Native Americans have grown up without the benefit of a loving home environment that, in turn, affected how they raised their children. Alcoholism and substance abuse issues have impacted generations of Native Americans, affecting family structure, economic stability and health (2). Another issue gaining more visibility is violence against Indigenous women, which is the third leading cause of death for Native American females ages 10 – 24 (3). Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women groups are advocating for these women and families to provide increased knowledge, support and resources to help address this urgent issue.

Complicating the impact of generational trauma is a healthcare landscape unique to Native Americans. In exchange for land ownership, treaty agreements and the U.S. Constitution have obligated the federal government to provide healthcare to tribal citizens (4). The federal agency charged with this responsibility, the Indian Health Service (IHS), provides healthcare to federally recognized sovereign tribes across the United States; however, it has been continuously underfunded to meet the needs of tribal members (5). In many rural areas, IHS has difficulties recruiting and retaining quality staff, impacting access and providing the quality of care needed. Staffing inadequacies further impact trust and quality of healthcare when providers cannot speak the language and do not understand tribal culture and etiquette.

In many rural areas, the only healthcare system available may be the Indian Health Service (IHS). Transportation concerns may make access to some services unattainable for some Native Americans. Furthermore, rural tribal members may need to travel hours to see a specialist or if they need a higher level of care. Under-funding means that care is rationed and services accessible to mainstream society, such as cancer screenings and hospice, are often simply not available on reservations. Case managers’ awareness of these health disparities will be essential when identifying potential resources and support to meet the needs and concerns of Native American patients.

Many Native Americans face social determinants of health deficits in the domains of education, transportation access, poverty, food insecurities, lack of employment opportunities, sub-standard housing and lack of access to quality health services influence the health disparities in Native American communities. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, infant mortality among Native Americans is almost double that of non-Hispanic whites. Native American mothers are three times as likely to receive late or no prenatal care (6). Native Americans are three times more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes (7) and 50% more likely to be diagnosed with coronary heart disease (8). For adolescents and young adults, suicide, homicide and unintentional injuries all contribute to higher mortality rates in Native Americans (9).

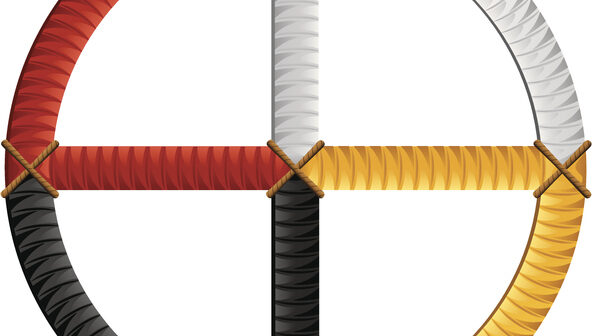

It is important for case managers to understand traditional Native American healing principles to best manage holistic healthcare needs. Native Americans embrace holism and the Medicine Wheel — looking at the individual as a whole and then understanding where there are deficits spiritually, physically, mentally and emotionally. While many tribes practice traditional medicine and healing practices today, specifics can vary based on the individual tribe:

- Purification – The Native American recognition of the connection between cleanliness and health in all dimensions of the Medicine Wheel. Practices include cleansings, blessings, fasting, abstentions (e.g., from certain foods, alcohol, sexual activity) and prayers.

- Medicine – Recognition of the restorative power of both healers (nurses, priests or medicine men, midwives) and therapeutics (often applied by nurses). This can involve smudging, massage, sweat lodges, medicinal botanicals and herbs. The four sacred plants are sage, sweetgrass, cedar and tobacco.

- Women’s healing networks – Intergenerational caring for families approached with understanding of community, the environment and the four dimensions of the Medicine Wheel.

- Wellness – The concept that some women are gifted with special abilities to keep the tribal community healthy as opposed to treating illness. Western observers often characterized these practices such as concocting special teas as “primitive.” Practices were frequently hidden out of concern that they would be disrupted, but also because the knowledge was considered a sacred gift and therefore closely guarded (10).

So, in providing care for Native American populations, what is a case manager to do? Delivering holistic and patient-focused care is the core of case management practice. Case managers are well equipped to lead the way in applying the transformational power of cultural humility, which leads to the provision of culturally sensitive healthcare.

It is important to distinguish cultural humility from cultural sensitivity. Cultural humility refers to the ongoing process of self-reflection and recognizing that an individual’s culture is uniquely personal and dynamic even among individuals of the same ethnicity, race, age, location, etc. Trusting and respectful relationships can be formed when the case manager starts with a mindset of cultural humility (11). Then, this paves the way for culturally sensitive care, which is utilizing specific interventions that demonstrate an awareness and an appreciation of the patient’s values, traditions and beliefs that are relevant to their needs and expectations (12).

Culturally sensitive care can serve to break through the unique walls and barriers standing between you and your patients. Purposeful and compassionate interventions help build relationships founded on trusting and transformative rapport rather than pain and mistrust.

Recommendations:

- Approach and assess the Native patient holistically through a lens of curiosity and respect for them as an individual AND a part of the Native community. Ask about and listen to their beliefs and honor those choices in your approach to patient care — the essence of cultural humility.

- Assess the individual’s mental, physical and social health status with the understanding that these are closely intertwined. Goals and interventions need to be triaged based on what the patient feels is most important.

- Self-reflect on your own beliefs. Assess how these beliefs influence your perception of Native traditions, spiritual beliefs, attitudes and challenges.

- Reach out to local Native communities and learn about the specific challenges they face as well as how they feel and process the impact of the greater Native American experience.

- Be patient and prepared to work to earn and build trust. Building a relationship may take longer. Hundreds of years of atrocities such as genocide, starvation, sterilization without knowledge, displacement, removal of and torture/murder of children, forced assimilation and severe punishments for practicing Native traditions have resulted in trauma and mistrust of those outside of the Native community. Mistrust can run deep and is not a reflection on the individual case manager, but rather a self-protective mechanism against the majority of society.

- Kinship may be different from how you define it. Know that elders, in general, may be considered grandparents and that care of children is often a communal responsibility. You may experience strong involvement from extended family when caring for an individual.

- Communication may be very different than you are used to.

- Storytelling is a valued communication style. You may hear stories that help give you insights and, conversely, telling a story can forge a connection.

- Native Americans tend to communicate in ways that are much more measured, reserved and collaborative. Get comfortable with periods of silence. Practice politeness and patience.

- Take guidance from what you have learned about the tribe you are connecting with. Individual tribes can have specific ways of communicating that signal respect such as maintaining a certain physical distance/personal space, using soft, gentle speech, little facial expression or minimal eye contact.

- Be sensitive to any educational barriers. Incorporate an evaluation of understanding teaching interventions using techniques such as patient/family demonstration or “teach back.”

- Be willing to work with and learn from the Native community leaders, healers and elders. Show them respect as they hold places of honor within Native communities. They can help you understand tribal customs, traditions and beliefs and provide you with information on any tribal programs to help with social determinant of health barriers.

- Advocate for the Native patient and support, encourage and empower them to be self-advocates. According to Indian Health Services, “Native Americans have a life expectancy that is 5.5 years less than U.S. non-natives due to poverty, inadequate education, discrimination in healthcare delivery system and cultural differences” (13).

- If you have an experience with one tribe, you only have experience with that one tribe! Remember to not assume that all tribal cultures are the same.

In case management, advocacy is a key component in ensuring that patient needs are met. By learning more about culturally sensitive case management for Native American individuals, you are also increasing awareness of systemic issues that propagate racism and power imbalances. To focus solely on individual patient needs can mean missed opportunities to confront the status quo and disrupt widespread racism. We invite you to continue a journey of discovery of Native American culture and traditions to enhance case management effectiveness. As Margaret P. Moss, editor of the seminal textbook American Indian Health and Nursing concluded, “…nurses and others who have committed to American Indian health hold several keys to doors unopened” (14).

References

- Chung, Christine. “Researchers Identify Dozens of Native Students Who Died at Nebraska School.” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/17/us/native-american-boarding-school-deaths-nebraska.html 17 November 2021. Accessed 5 August 2022.

- Brown-Rice, Kathleen. “Examining the Theory of Historical Trauma Among Native Americans.” The Professional Counselor, 3, issue 2, https://tpcjournal.nbcc.org/examining-the-theory-of-historical-trauma-among-native-americans/. 15 October 2014, Accessed 8 August 2022.

- Family and Youth Services Bureau, “NIWRC Spotlights Critical Issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW).” S. Department of Health & Human Services, 25 May 2022, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/fysb/news/niwrc-spotlights-critical-issue-missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women-mmiw , Accessed 8 August 2022.

- Indian Health Service, “Basis for Health Services.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/basisforhealthservices/. January 2015, Accessed 2 August 2022.

- Villegas, Andrew, “Underfunding and Access Are Barriers To Healthcare For Native Americans, Especially On The Reservations.” Kaiser Health News in Collaboration with National Public Radio, Healthcare Finance. https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/underfunding-and-access-are-barriers-healthcare-native-americans-especially-reservation#:~:text=The%20IHS%20is%20chronically%20underfunded.%20It%20receives%20a,expect%2C%20such%20as%20emergency%20departments%20or%20MRI%20machines. 14 April 2016. Accessed 2 August 2022.

- “Infant Mortality and American Indians/Alaska Natives.” S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlID=38 1 March 2021. Accessed 8 August 2022.

- “Diabetes and American Indians/Alaska Natives.” S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=33, 1 March 2021. Accessed 8 August 2022.

- “Heart Disease and American Indians/Alaska Natives.” S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=34, 11 February 2021. Accessed 8 August 2022.

- “Mental and Behavioral Health – American Indians/Alaska Natives.” S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=39, 19 May 2021. Accessed 8 August 2022.

- Moss, Margaret P., Editor. American Indian Health and Nursing. Springer Publishing Company, 2016, pp. 33-41.

- Kahn, Shamiala. “Cultural Humility vs. Cultural Competence – and Why Providers Need Both.” HealthCity Newsletter, Boston Medical Center, https://healthcity.bmc.org/policy-and-industry/cultural-humility-vs-cultural-competence-providers-need-both 9 March 2021. Accessed 7 August 2022.

- Tucker, CM, Marsiske, M, Rice, K, Jones, J., Herman, K C, “Patient-Centered Culturally Sensitive Health Care: Model Testing and Refinement.” Health Psychol. 30 no. 3 May 2011. pp. 342 – 350. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3092156/ Access 8 August 2022.

- “Disparities.” Indian Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Humana Services.” https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/, October 2019. Accessed 7 August 2022.

- Moss, Margaret P., Editor. American Indian Health and Nursing. Springer Publishing Company, 2016, p. 352.

Carole Gescheidle, MSOLQ, BSN, RN, is A Registered First Generation Descendant of the Menominee Nation of Wisconsin and clinical strategy and practice lead at Humana.

Teena Manning, BSN, RN, CCM, is a Descendant of the Choctaw and Cherokee Nations and senior nursing educator at Humana.

Julia Mayer, BSN, RN, CCM, is a Registered Member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and care manager, telephonic nurse 2 at Humana.

Julia Mayer, BSN, RN, CCM, is a Registered Member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and care manager, telephonic nurse 2 at Humana.